"Biển cả lớn vì nó chấp nhận mọi dòng chảy; sông suối cao vì nó thấu hiểu sự giảm sút."

Lão Tử

VCS là ví dụ điển hình của một doanh nghiệp tốt bị ảnh hưởng tiêu cực bởi tình hình kinh tế toàn cầu suy giảm. Trong quá khứ, doanh thu hàng năm của công ty dao động từ 5 đến 7 ngàn tỷ đồng, nhưng đến năm 2023, con số này chỉ còn 4.3 ngàn tỷ đồng. Lợi nhuận sau thuế đã giảm mạnh từ 1.4 đến 1.7 ngàn tỷ/năm xuống chỉ còn hơn 800 tỷ đồng.

Biên lợi nhuận gộp đã giảm từ mức cao nhất là 35%/năm xuống còn 28% vào năm 2023. ROE cũng giảm từ 35% vào năm 2021 xuống còn 15% vào năm 2023.

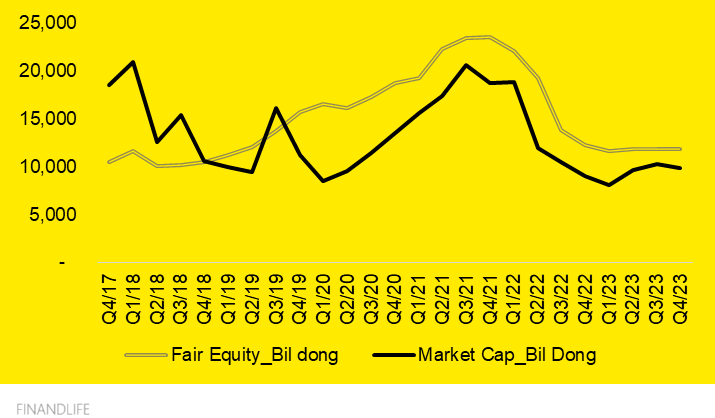

Vốn hóa thị trường của công ty cũng giảm mạnh, từ 18 đến 19 ngàn tỷ xuống còn hơn 9 ngàn tỷ, tức giảm gần 50%. Giá cổ phiếu giảm từ 110 ngàn đồng xuống còn 61 ngàn đồng.

Theo giải trình KQKD năm 2023, ngành bất động sản và xây dựng tại các thị trường chính của VCS, như Mỹ và Châu Âu, tiếp tục chịu ảnh hưởng tiêu cực từ lãi suất, lạm phát và giá vật liệu xây dựng cao. Tình hình cạnh tranh ngày càng gay gắt cũng là một yếu tố ảnh hưởng đến doanh thu của công ty.

Tuy nhiên, năm 2024, dự kiến rằng bối cảnh lãi suất sẽ ổn định hơn và lạm phát không còn quá cao, điều này có thể giúp tình hình kinh doanh của công ty trở nên tích cực hơn. Biên lãi gộp đã bắt đầu tăng từ mức thấp nhất là 26% trong quý 1/2023 lên 30% vào quý 4/2023. Tồn kho được duy trì ổn định và công ty không có nợ nần gì.

Công ty duy trì chính sách chi trả cổ tức tiền mặt trung bình đạt 50% lợi nhuận sau thuế, với mức trung bình là 4000 đồng/cp. Nếu kinh doanh quay lại mức trước đây, suất sinh lãi cổ tức đạt 7%/năm, hấp dẫn.

Dựa trên các dữ liệu kinh doanh và tài chính, giá trị hợp lý của vốn hóa thị trường (theo số liệu của năm thấp điểm 2023) ước đạt 11,850 tỷ đồng, cao hơn 21% so với vốn hóa thị trường hiện tại. Nếu kinh doanh của công ty quay lại như trước đây, giá trị hợp lý của vốn hóa thị trường có thể đạt 20 ngàn tỷ đồng, gấp đôi so với vốn hóa thị trường hiện tại.

Ý tưởng đầu tư:

Mua vào một doanh nghiệp sản xuất đá nhân tạo hàng đầu thế giới với giá trị thực cao hơn 20% so với giá thị trường trong kịch bản tiêu cực nhất, và cao hơn 100% so với giá thị trường trong kịch bản kinh doanh quay trở lại như trước. Mỗi năm nhà đầu tư còn được 7% suất sinh lãi cổ tức bằng tiền mặt.

FINANDLIFE