The Vietnamese market still looks an attractive destination for investment despite the risks hovering around the wider region. International investors in Asia-Pacific and emerging markets in general have been put on high alert after widespread civil unrest in Sri Lanka which culminated in the resignation of the president and prime minister. The island nation has faced months of protests about the state of the economy, and on top of spiralling food and fuel prices it is struggling with a huge interest bill on its foreign-currency debt. Unfortunately, Sri Lanka isn’t the only Asian country facing economic hardship and potentially a recession according to a survey of leading economists.

RISKS RISING

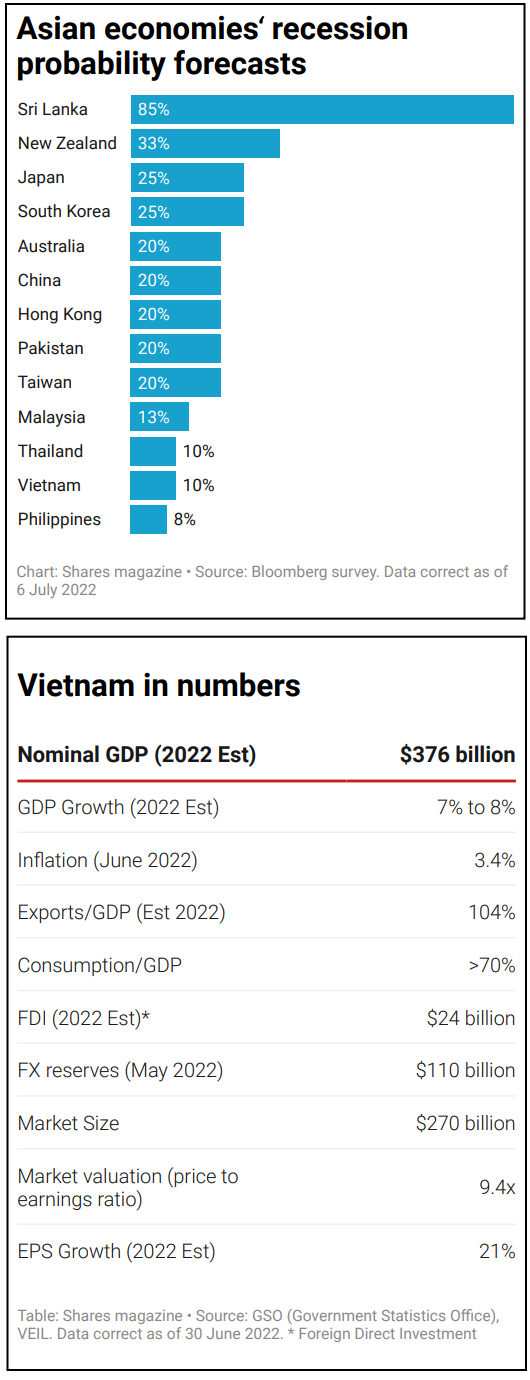

The latest poll by Bloomberg suggests while Sri Lanka has an 85% chance of falling into recession in the next year, up from a 33% chance in the previous survey, economists have also raised their expectations of recession across the region.

China and Taiwan have a one in five chance of entering recession in the next 12 months, as does Australia, while Japan and Korea have a one in four chance and New Zealand’s chances are one in three according to the survey. In fairness, Bloomberg Economics’ proprietary model gives the US a 38% chance of falling into recession in the next 12 months, compared with zero chance at the start of the year.

However, unlike the US, what is compounding investor worries about Asian economies is their high external debt levels and the risk of default.

MOUNTAIN OF DEBT

Emerging economies around the world could be on the precipice, according to Bloomberg, with a pile of close to $240 billion of distressed debt ‘threatening to drag the developing world into an historic cascade of defaults’. Lebanon stopped paying foreign bondholders for the first time in March 2020, followed by Sri Lanka this May and Russia last month.

The cost of insuring emerging market debt against non-payment has rocketed since Russia invaded Ukraine, with Egypt, Ghana, Pakistan and Tunisia all seen all vulnerable to default. Even countries like Argentina, which has an estimated 74% ratio of government debt to GDP (gross domestic product) and whose sovereign bonds yield close to 21%, could be drawn into the downward spiral. ‘With low-income countries, debt risks and debt crises aren’t hypothetical. We’re pretty much already there’, said World Bank chief economist Carmen Reinhart on Bloomberg TV.

Of the $1.4 trillion of outstanding emerging market sovereign debt priced in dollars, euros or yen, around a fifth is trading at ‘in distress’, which means they are yielding more than 10% above US Treasuries with similar maturities, indicating potential default.

The concern among economists is that there could be ‘contagion’ or a domino effect if foreign bondholders decide to pull the plug, as has happened in previous crises. Markets which on the face of it have no connection with each other could start to topple simply because investors start taking money out with no warning, as happened during the Asian crisis of the late 1990s and the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s.

The current crisis is reminiscent of the 1980s, as rapid interest rate rises by the Federal Reserve to curb inflation are forcing the dollar higher, adding to the pain for developing countries already struggling to service their foreign debt. Many emerging economies rushed to sell foreign-denominated bonds during the Covid pandemic when interest rates were rock bottom and their borrowing needs were high, but with central banks in the US and Europe raising rates capital is draining out of these markets again.

Now, with food and energy prices soaring and the threat of more political turmoil, some countries may decide, somewhat understandably, that what little reserves they have would be better off spent helping their own citizens rather than repaying foreign bondholders.

NOTABLE EXCEPTION

One country which isn’t on the list of potential defaulters and has just a 10% risk of entering recession in the next 12 months, according to Bloomberg, is Vietnam. A so-called ‘edge’ market, because it borders China, Vietnam has a growth record most nations would be proud of, a low debt to GDP ratio and plenty of foreign currency reserves.

GDP rose by 7.7% in the second quarter, the strongest April-June increase since 2011, bringing first half growth to 6.4% and leading international economists to raise their full-year estimates. Industrial production for the first half rose by 8.5%, while exports increased by 17.3% to $186 billion creating a small trade surplus.

Meanwhile, the ratio of sovereign debt to GDP is just over 40%, lower than China (78%) and South Korea (52%), as the government resisted splurging on welfare and social spending during the pandemic unlike other Asian countries.

Having been badly affected during the global financial crisis, fiscal discipline and monetary stability are now ingrained. Vietnam is also one of the few countries worldwide to enjoy positive real interest rates, as inflation is just 3.4%, although rising oil costs are pushing items such as transportation up by double digits.

Crucially, food price inflation isn’t an issue as the country is largely self-sufficient in basic foodstuffs such as rice, grains and fish, and it is a major exporter of agricultural products to the US, China and Japan. Another positive for the nation is that, due to the breakdown in global supply chains following the sudden demand surge post-pandemic, there has been a record increase in foreign direct investment this year.

Among others, US tech giant Apple (AAPL:NASDAQ) is relocating iPad manufacturing from China to Vietnam while Chinese smartphone maker Xioami has opened a new plant in the country. As a result of its economic growth and success in attracting foreign investment, S&P Global Ratings upgraded Vietnam’s long-term sovereign credit rating in May from BB to BB+ with a stable outlook, one notch below investment grade.

VALUE OPPORTUNITY

Despite its strong economic performance, however, the Vietnamese stock market has been a victim of the unwinding of global risk positions with the Ho Chi Minh stock index down nearly 22% year to date. Dien Vu, manager of UK-listed investment trust Vietnam Enterprise Investments Limited (VEIL), argues the biggest stocks in the market are growing their profits by more than 20% this year, putting the index at a five-year valuation low of nine times prospective earnings.

On the one hand it’s reasonable to expect economic growth to moderate in the second half, while inflation could continue to creep up. However, with oil making up more than half of the increase in inflation the recent fall in crude as a result of demand destruction in markets like the US should be enough to offset rising material input prices.

There could also be a major catalyst for the market down the road when the global index compilers like MSCI and S&P finally put Vietnam on their emerging markets ‘watch list’. There are a couple of reasons why the country doesn’t yet feature in the emerging markets indices, the main one being the market isn’t open to foreign investors.

The simple reason for this is the government doesn’t want its much larger northern neighbor piling in and buying up large swathes of the economy. The regulator is in the process of allowing Vietnamese companies to issue non-voting depository receipts, or NVDRs, which will have the same dividends and rights as ordinary shares without a vote.

Vietnam’s prime minister is pushing hard to allow foreign investment in the market, which will go a long way to getting the country on the ‘watch list’. Once the country officially joins the emerging market indices, there will be a huge inflow of money as big global investors scramble for a piece of the pie.

BEAT THE CROWD

For UK investors, there are already a couple of ways to invest in Vietnam through London-listed, country-specific investment trusts which are all trading at a discount to net asset value, meaning they offer a ‘double discount’ to the market’s usual valuation.

The largest is Vietnam Enterprise Investments, which has £1.6 billion of assets and trades at a 20% discount to net asset value with an ongoing charge of 1.89%. This is followed by Vietnam Opportunity Fund (VOF) with £980 million of assets, also trading at a 20% discount and with an ongoing charge of 1.64%, and Vietnam Holding (VNH) with £104 million of assets, trading at a 16% discount with an ongoing charge of 2.52%.

DISCLAIMER: The author owns shares in Vietnam Enterprise Investments Limited.

By Ian Conway Companies Editor