Ray Dalio quản lý quỹ phòng hộ lớn nhất thế giới, Bridgewater Associates.

Quỹ có một số lượng người đầu tư và theo dõi khổng lồ nên khi Ray Dalio phát biểu về thị trường, mọi người thường lắng nghe.

Ngoài ra, Dalio cũng được biết đến như một trong những người am tường nền kinh tế trong lĩnh vực tài chính.

Như một phần xứ mệnh diễn giải nền kinh tế hoạt động ra sao, Dalio đã đặt sự diễn giải đấy gọn gàng trong một video hoạt họa 30 phút, cái được gọi là “cỗ máy kinh tế hoạt động thế nào”.

Chúng ta cùng theo dõi cái cách mà một nhà quản lý quỹ phòng hộ hàng đầu thế giới nhìn nhận về kinh tế:

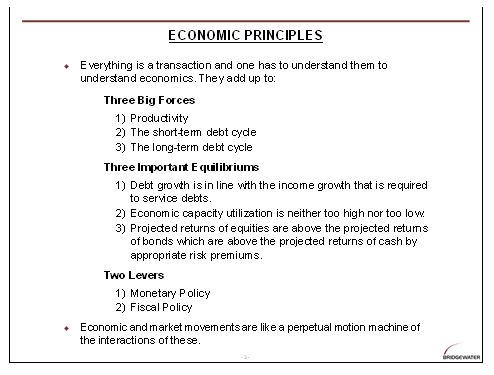

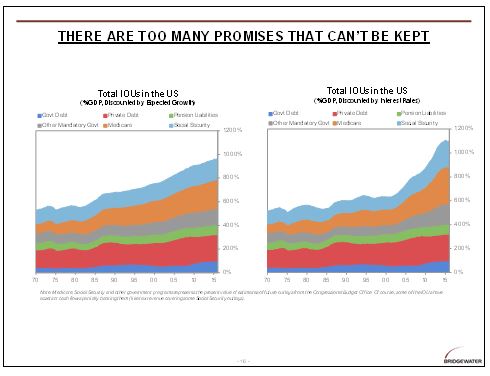

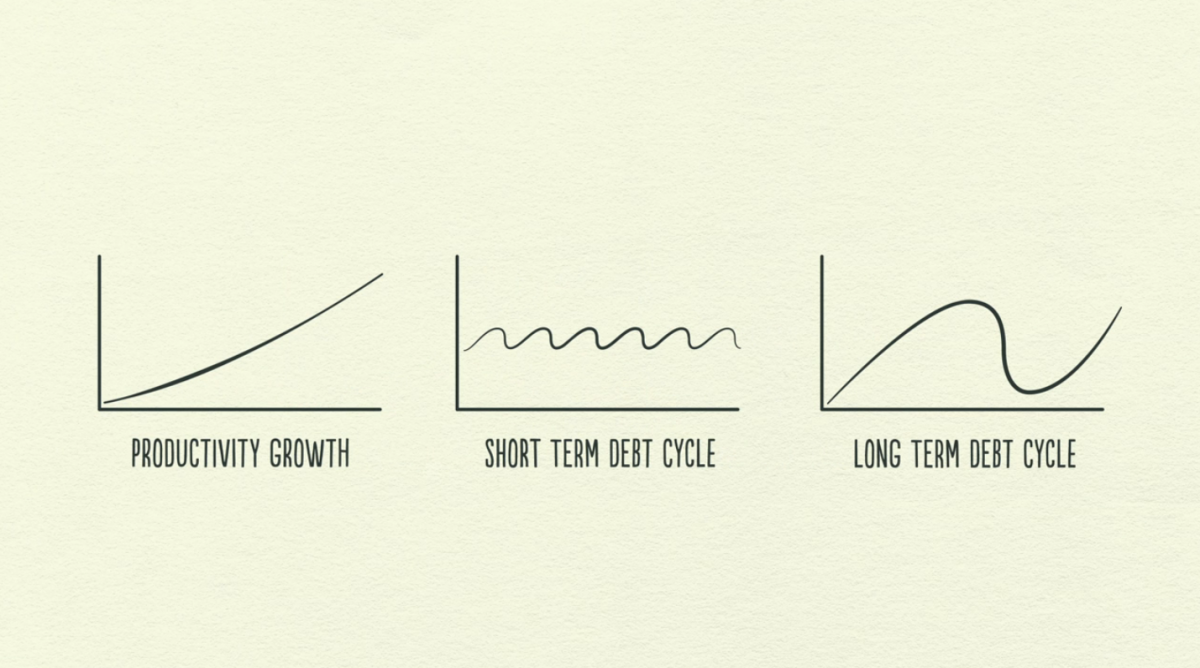

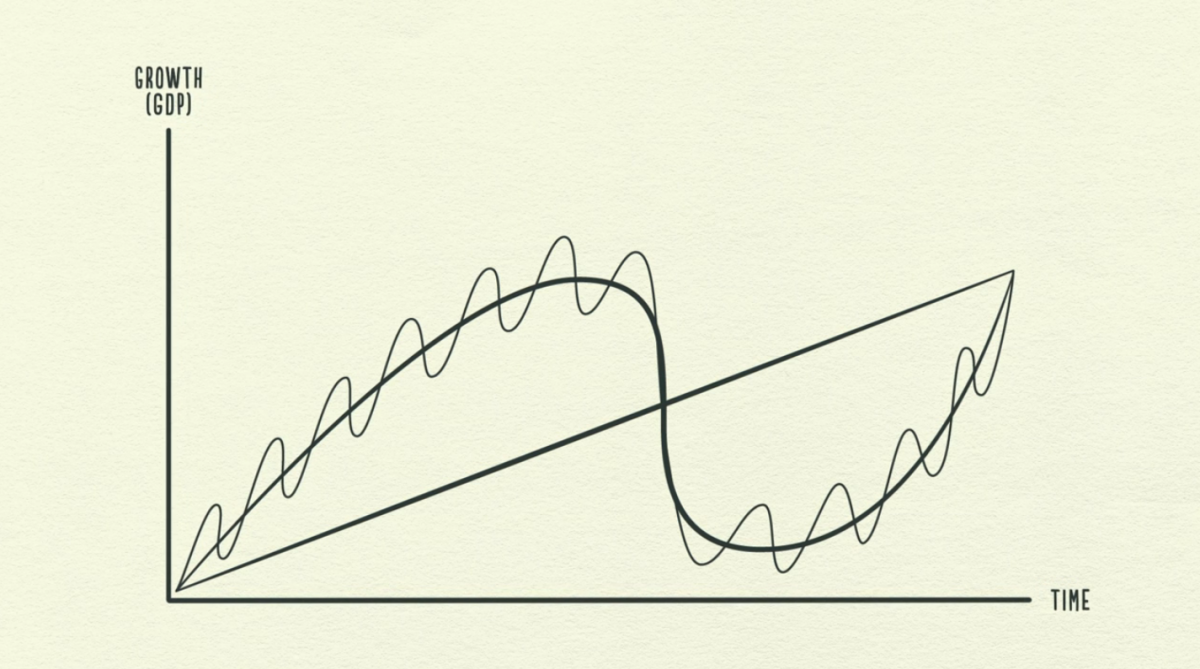

Có 3 lực cơ bản dẫn dắt nền kinh tế

These are the three main forces that drive the economy.

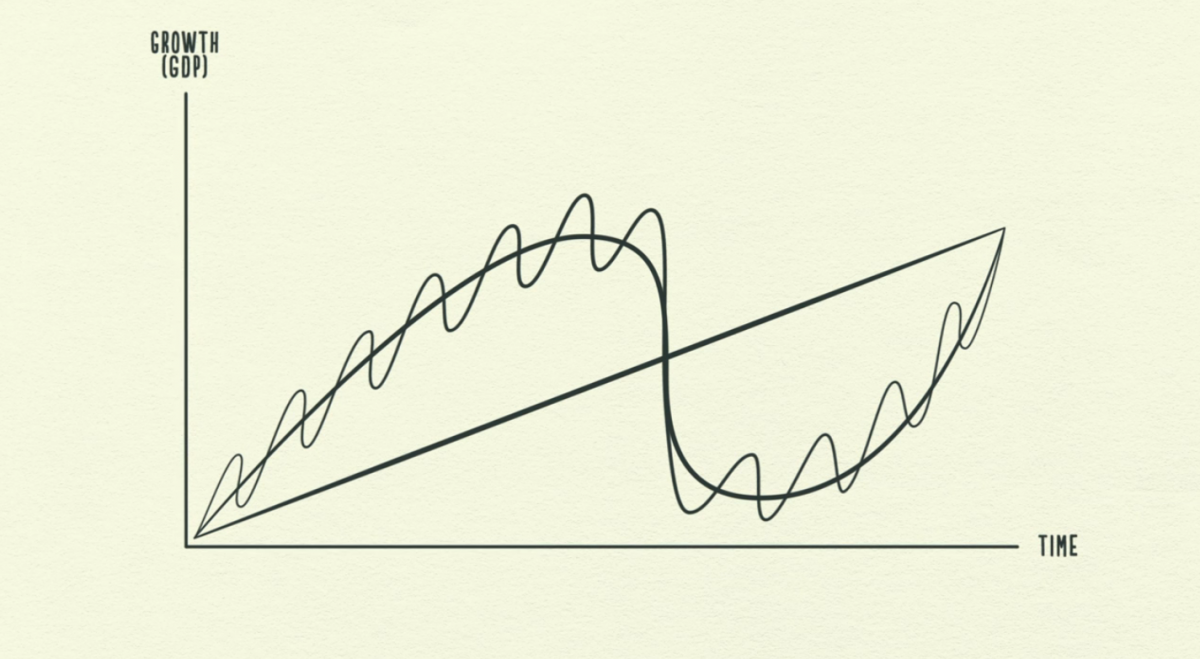

Đặt chúng lồng vào nhau sẽ chỉ ra chu kỳ kinh tế của chúng ta

Laying them on top of each other shows our economic "cycle."

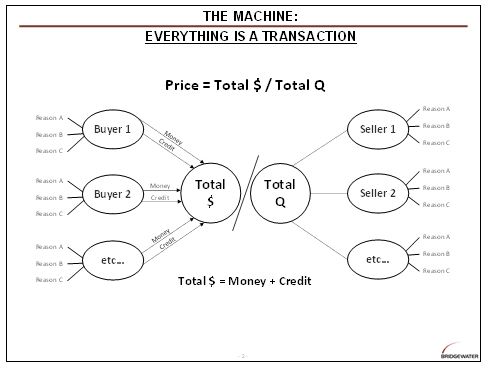

Giao dịch là nền tảng của nền kinh tế. Đơn giản là mua và bán – chúng ta giao dịch mọi lúc

Transactions are the bedrock of the economy. It's simply buying and selling — we make transactions all the time.

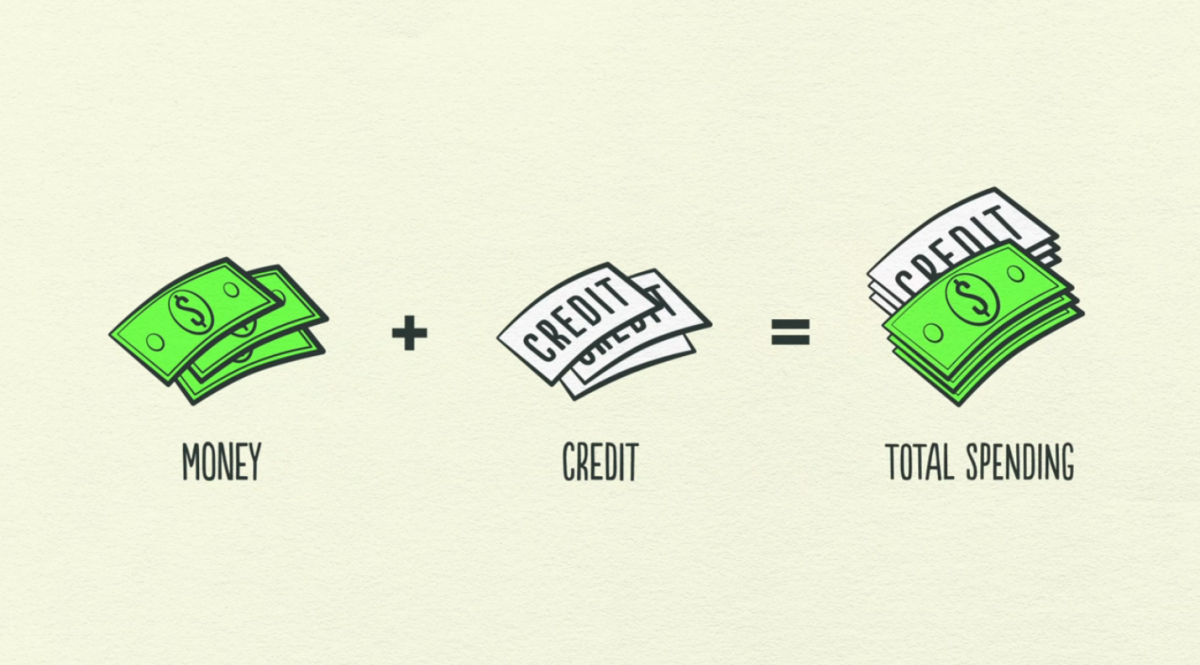

Bạn có thể giao dịch với tiền của bạn hay là tín dụng, và đó là tổng chi tiêu của bạn

You can make a transaction with money or credit, and that gives you the total spending.

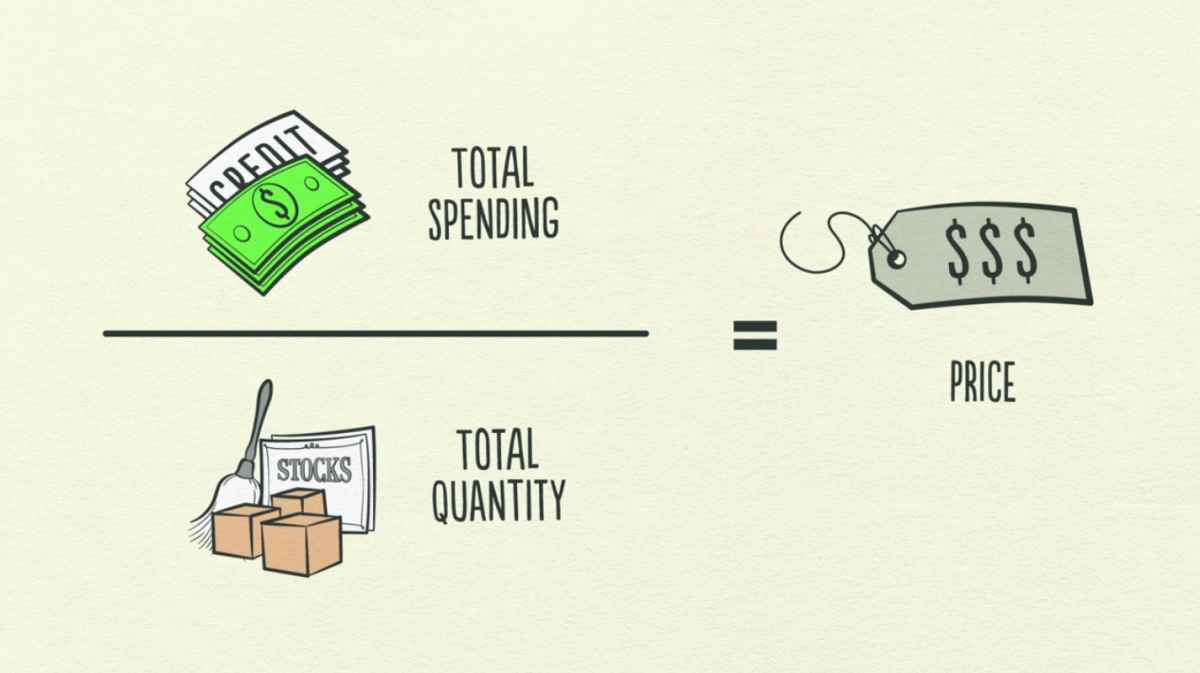

Nếu bạn lấy tổng chi tiêu và chia nó cho tổng sản lượng, chúng ta sẽ có giá. “Nếu chúng ta có thể hiểu mọi giao dịch, chúng ta có thể hiểu toàn bộ nền kinh tế” Dalio nói.

If you take total spending and divide it by the total quantity, we get price. "If we can understand transactions, we can understand the whole economy," Dalio says

Thị trường đơn giản là tất cả người mua và người bán giao dịch cùng một loại gì đó

A market is simply all the buyers and all the sellers making transactions for the same thing

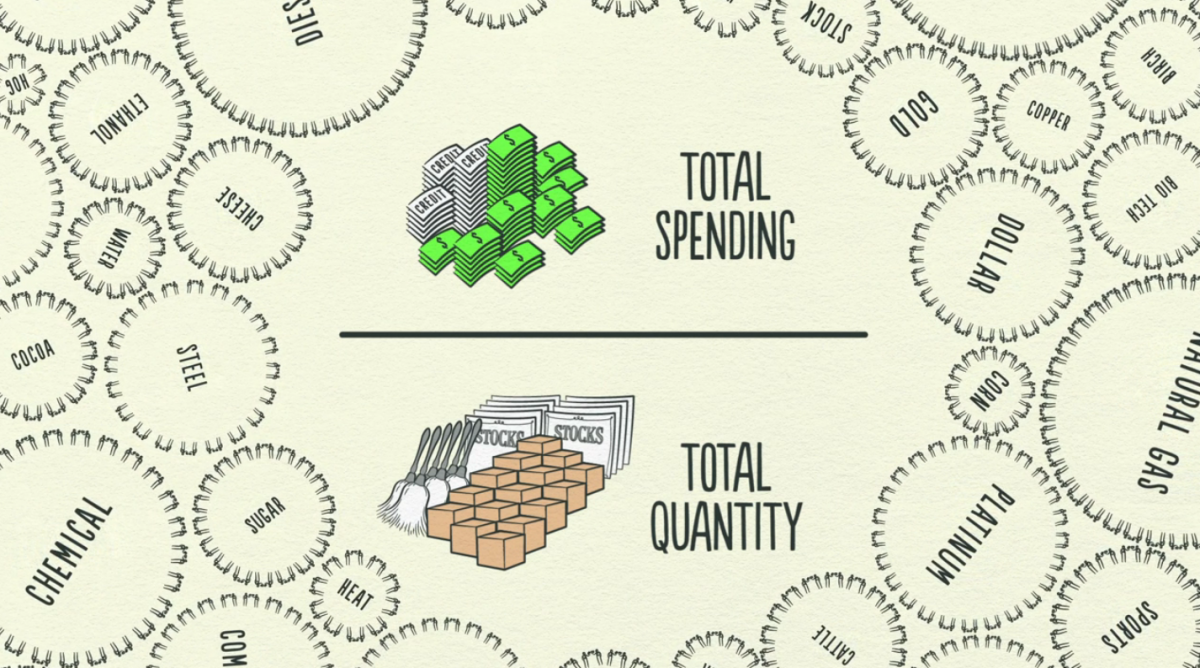

Có hàng triệu thị trường khác nhau, và nền kinh tế bao gồm tất cả những giao dịch trong tất cả thị trường đó

There are millions of different markets, and the economy consists of all transactions in all markets

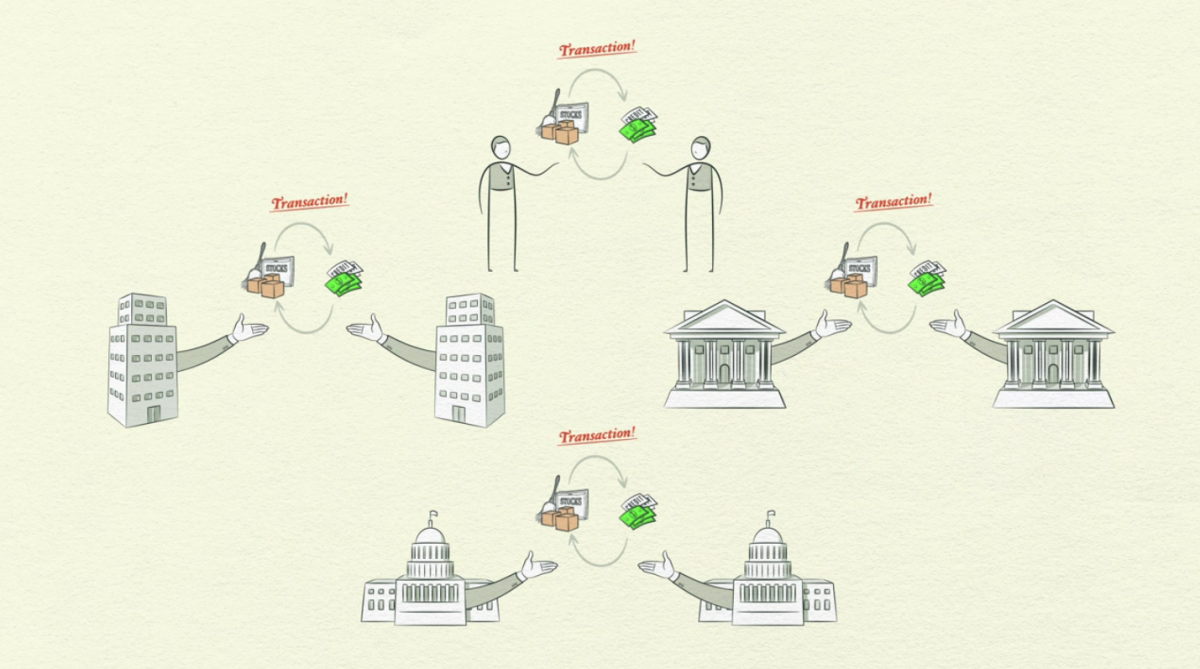

Con người, ngân hàng, doanh nghiệp và chính phủ tương tác với nhau thông qua giao dịch

People, banks, businesses and governments all interact via transactions

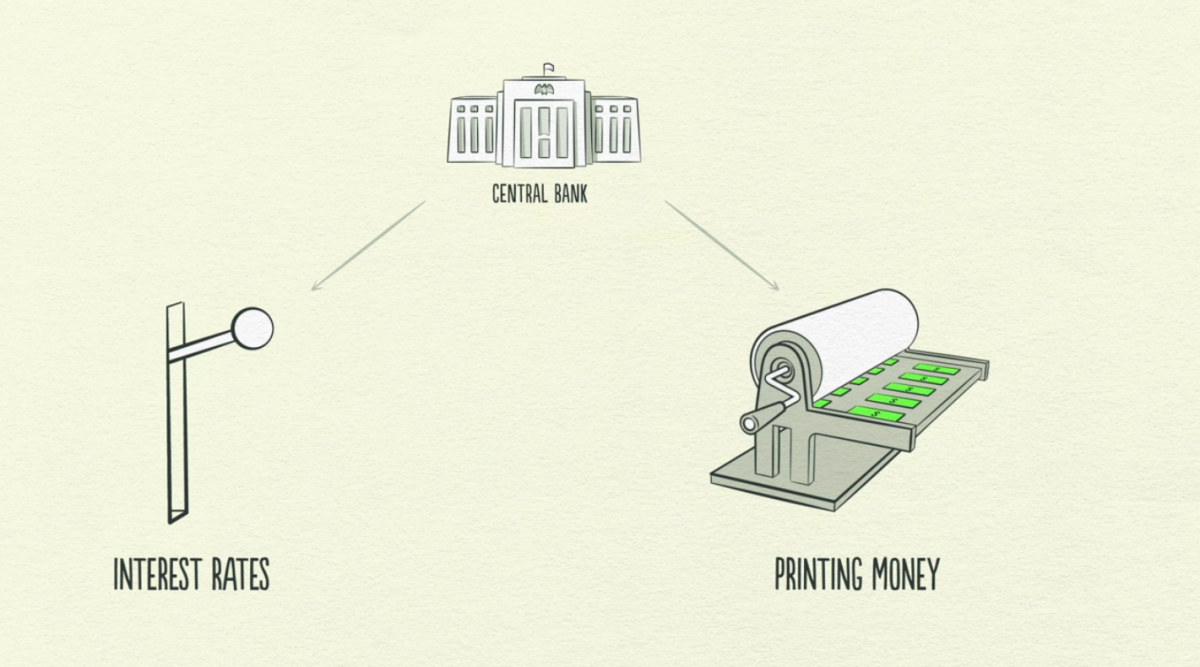

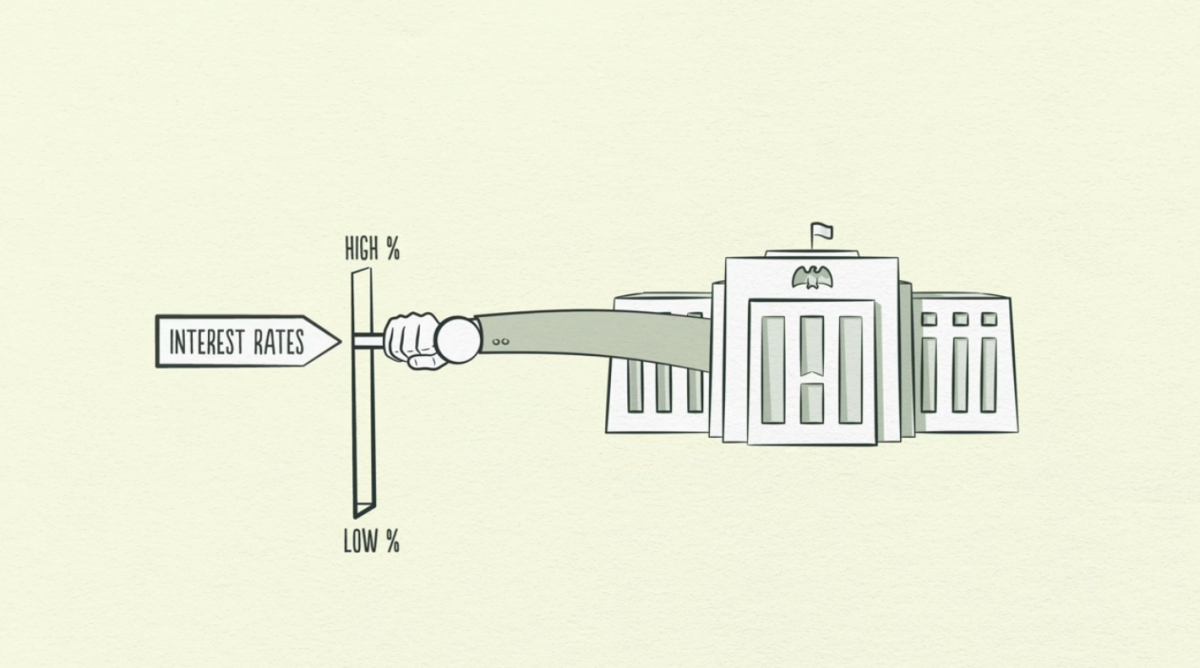

Tại trái tim của nền kinh tế là ngân hàng trung ương, tổ chức điều hành lãi suất và cùng tiền tệ. Theo đó, ngân hàng trung ương tác động đến dòng chảy tín dụng

At the heart of it is the central bank, which controls interest rates and the money supply. In so doing, the central bank impacts the flow of credit.

Và tín dụng là một phần thiết yếu

And credit is essential

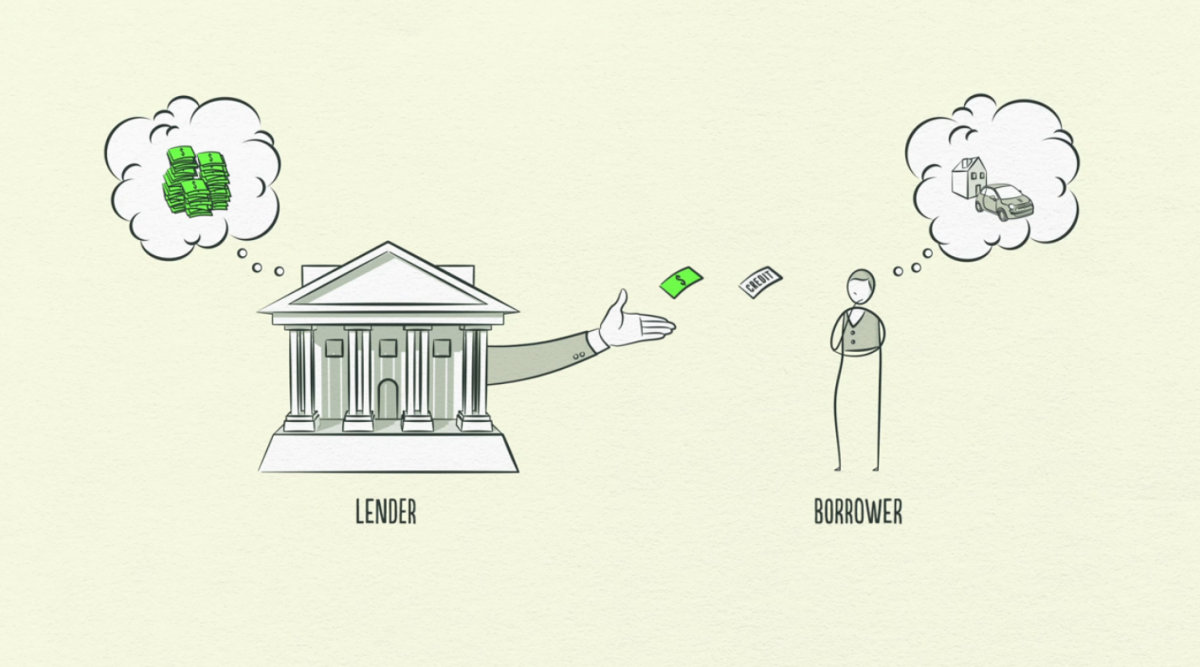

Nếu không có tín dụng, nền kinh tế hiện đại sẽ trông khác hẳn. Từ khi chúng ta có tín dụng, những người cho vay sử dụng nó để tạo thêm tiền và những người đi vay sử dụng nó để mua những thứ mà họ không có khả năng đáp ứng ở ngay thời điểm hiện tại.

Without credit, the modern economy would look very different. Since we have credit, lenders use it to make more money and borrowers use it to buy something they can't immediately afford

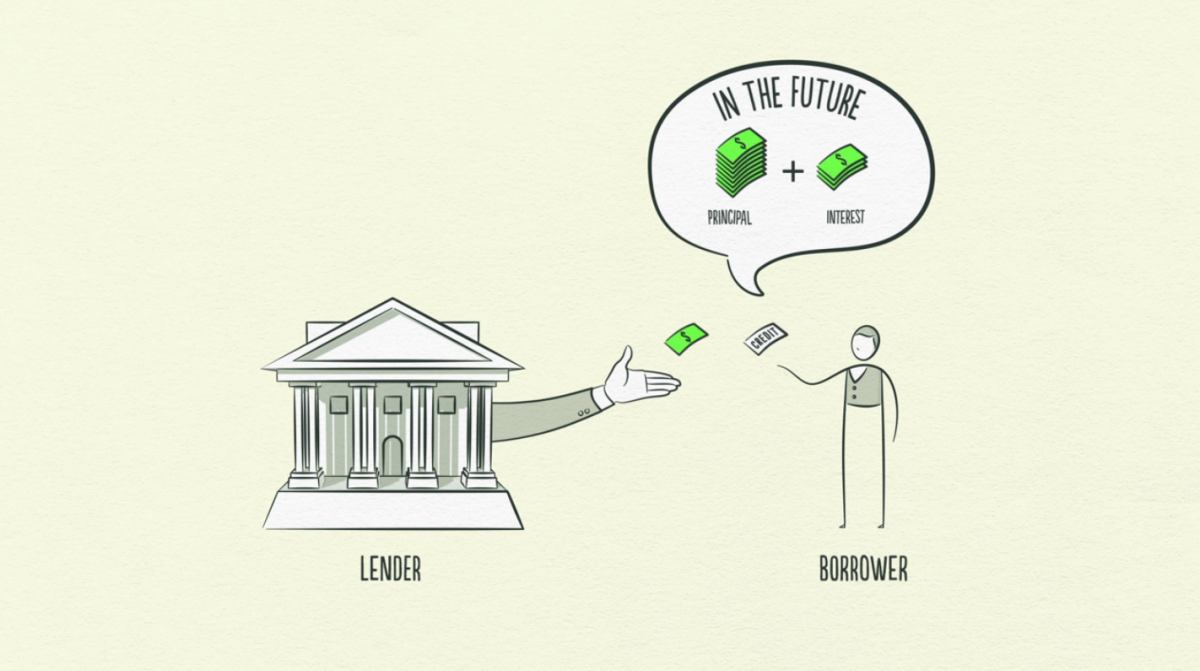

Những người đi vay hứa sẽ trả lại tiền vay trong tương lai và cũng trả tiền lãi trên khoản tiền vay đó

The borrower makes a promise to pay a loan back in the future and also pays interest on that loan

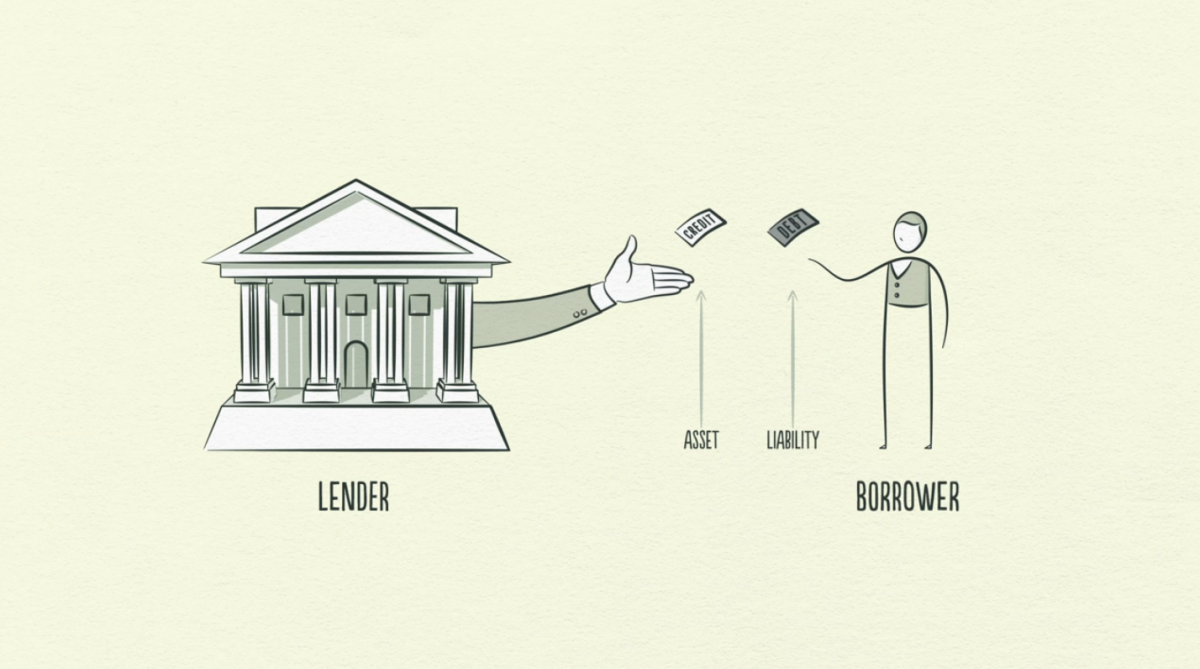

Ngân hàng mở rộng tín dụng cho người vay và sau đó chúng trở thành nợ

The credit the bank extends to the borrower then becomes debt

Nợ là một trách nhiệm cho người đi vay, nhưng nó lại là tài sản của ngân hàng.

Debt is a "liability" for the borrower, but it's an "asset" for the bank

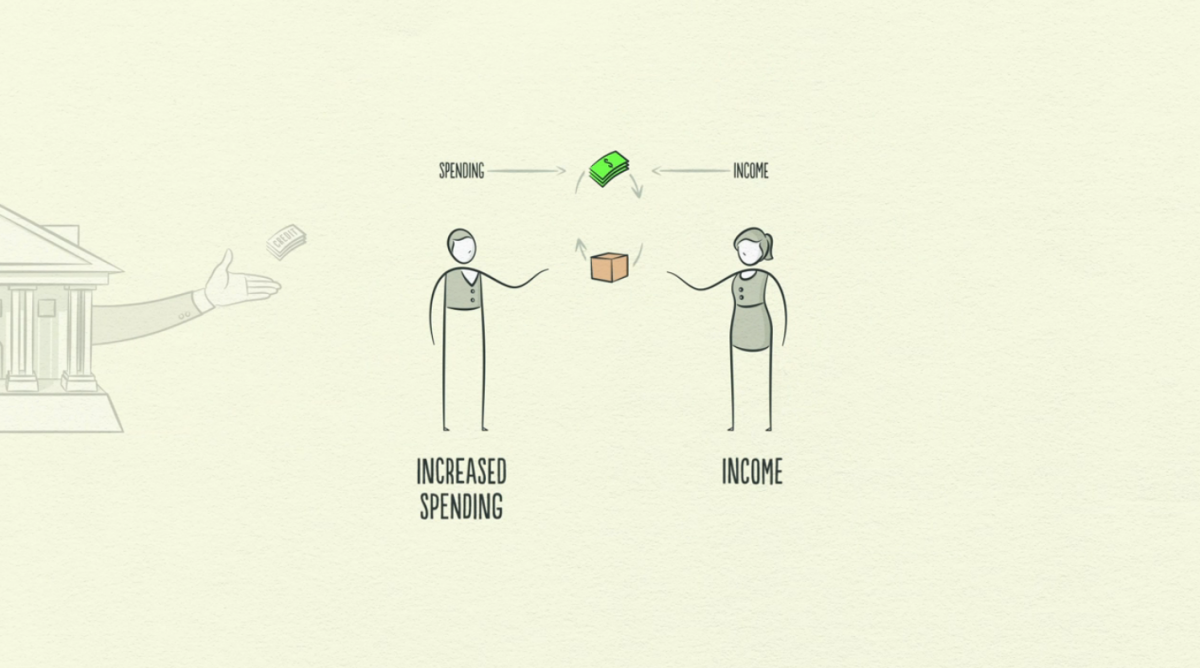

Trong ngắn hạn, càng nhiều tín dụng thì càng tốt cho nền kinh tế bởi vì chi tiêu của người này là thu nhập của người khác. Nếu càng nhiều người sử dụng tín dụng nền kinh tế sẽ tăng trưởng.

In the short term, more credit is good for the economy because one person's spending is another person's income. If more people have more money via credit, the economy grows

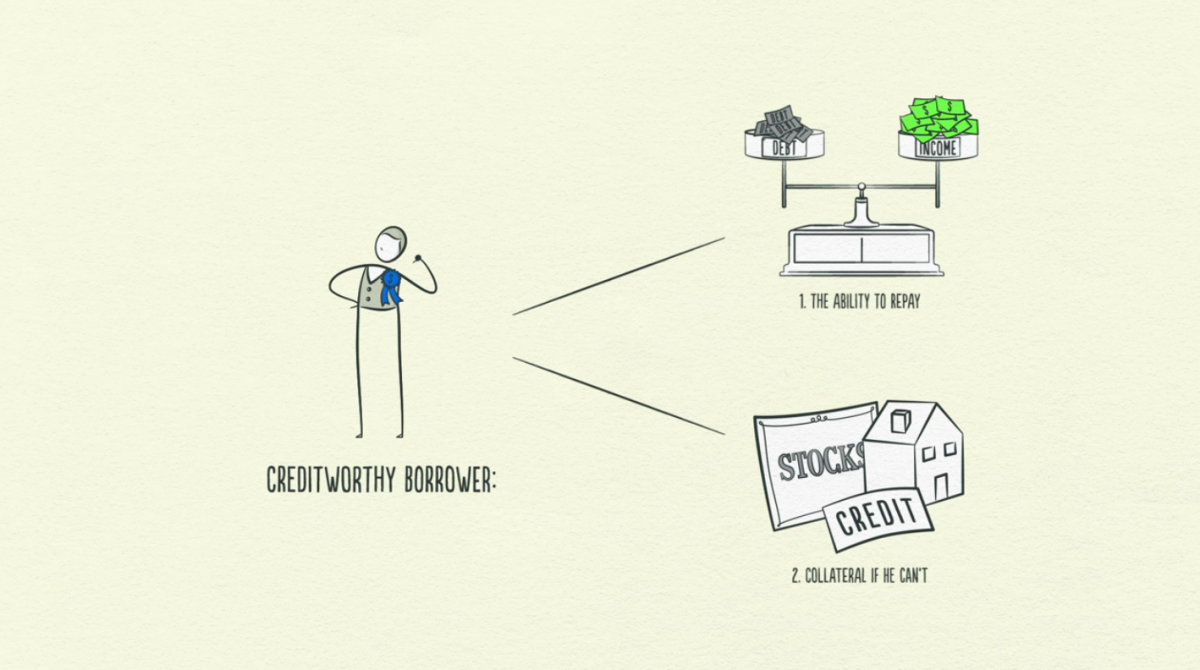

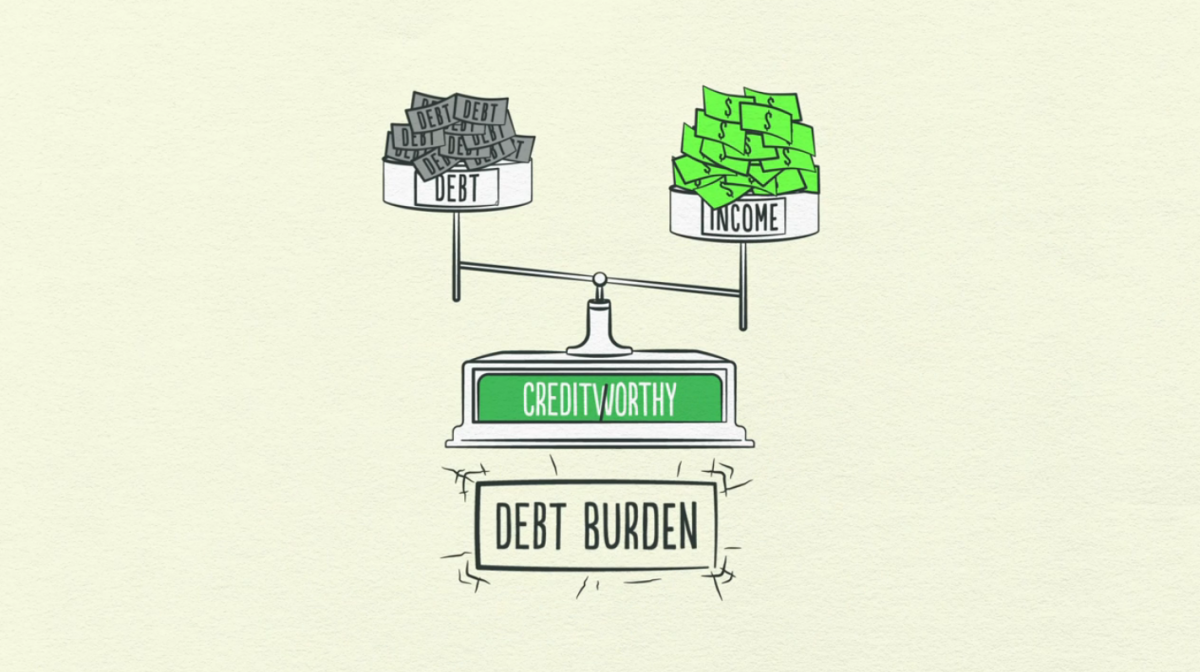

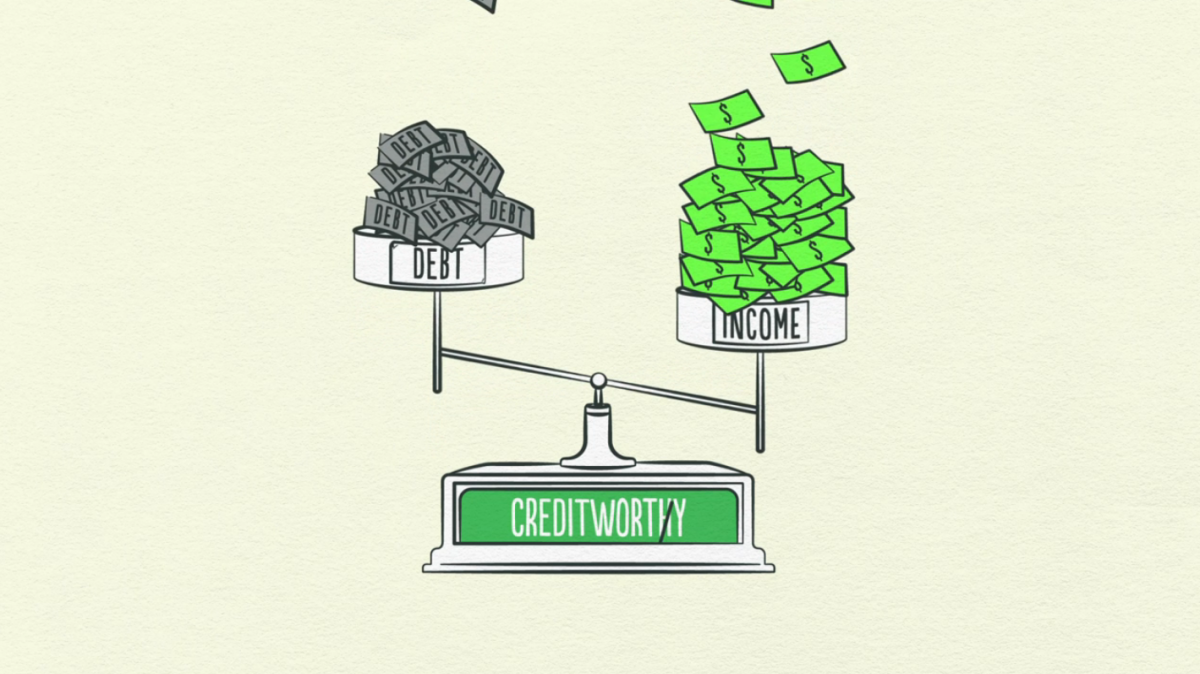

Vì vậy, một người đi vay có uy tín trả nợ là một ai đó thỏa 2 điều kiện: vừa có khả năng hoàn trả vừa có tài sản cầm cố, thế chấp

So a "creditworthy borrower" (someone banks should and will loan to) is someone who has both the ability to repay (income) and collateral just in case (a house, financial assets)

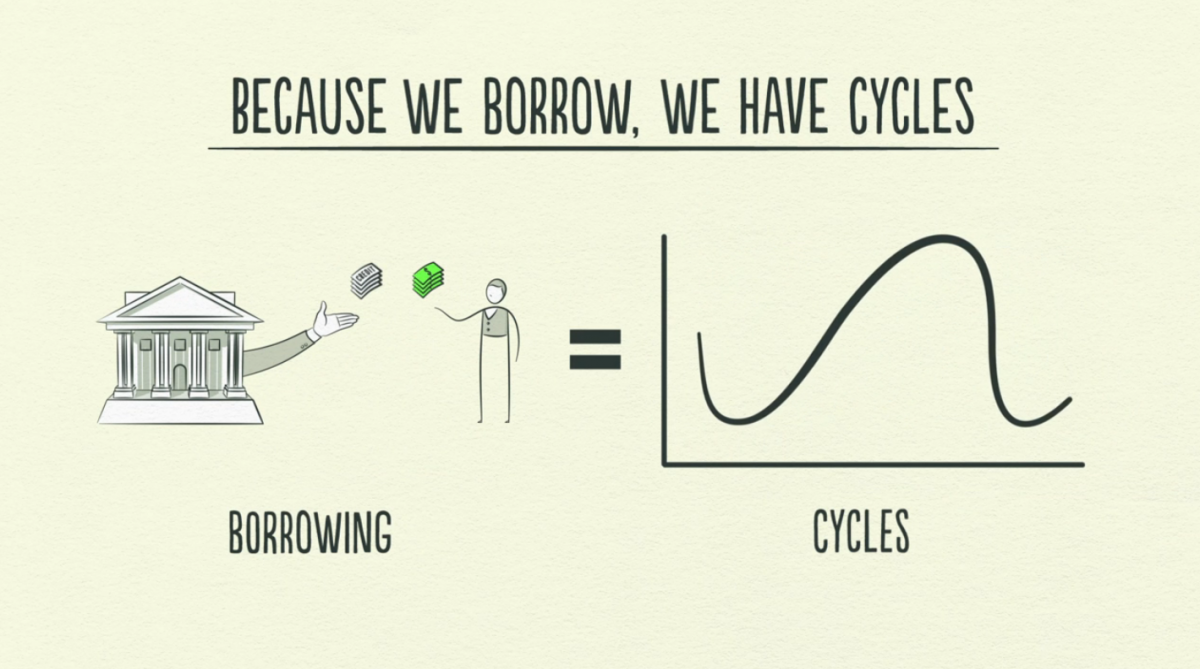

Hoạt động vay mượn tạo ra chu kỳ

The act of borrowing creates a "cycle."

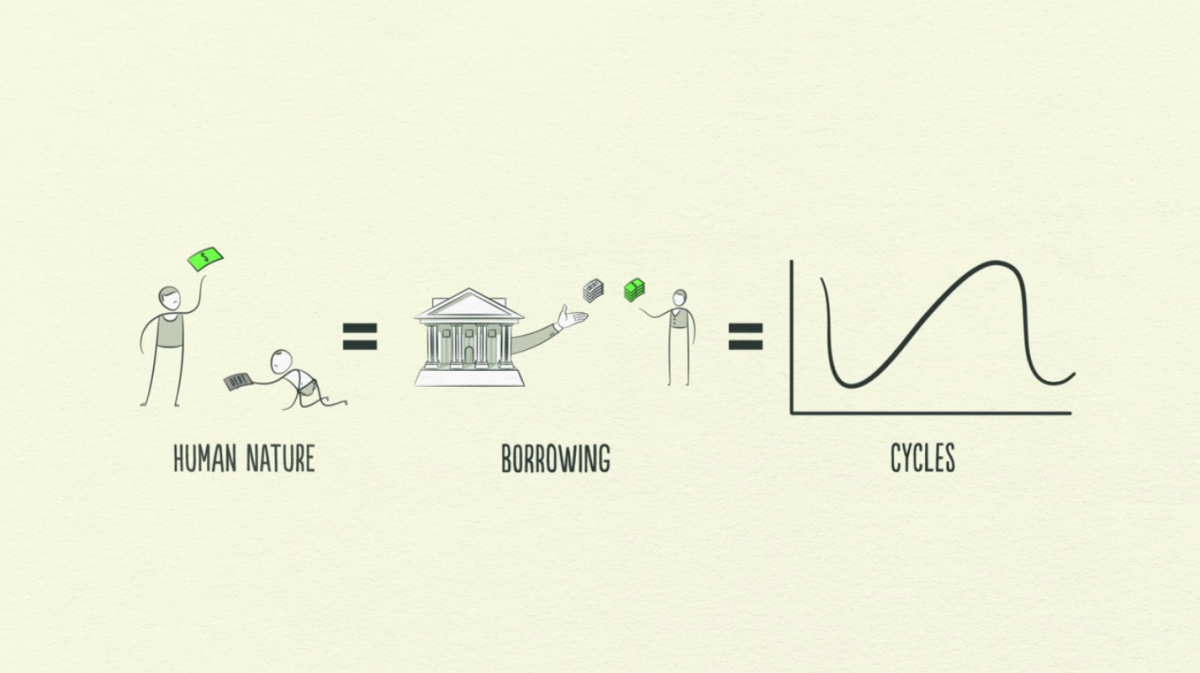

Vấn đề khi những người vay mượn đó quá gần với đường “chu kỳ nợ ngắn hạn” để thật sự hiểu tác động của những quyết định vay mượn

The problem is that borrowers are too close to the "short term debt cycle" line to really understand the impact of their borrowing decisions

Vấn đề tự nhiên của con người là họ muốn vay mượn để mua những thứ mà chúng ta muốn ở hiện tại. Cảm ơn tín dụng, chúng ta có thể luôn trả lại sau đó!

It is human nature to want to borrow to get the things we want now. Thanks to credit, we can always just pay it back later!

Thật khó để quay lại và nhìn nợ ngắn hạn với nợ dài hạn và sản lượng sản xuất.

It's hard to take a step back and see short-term debt versus long-term debt and productivity.

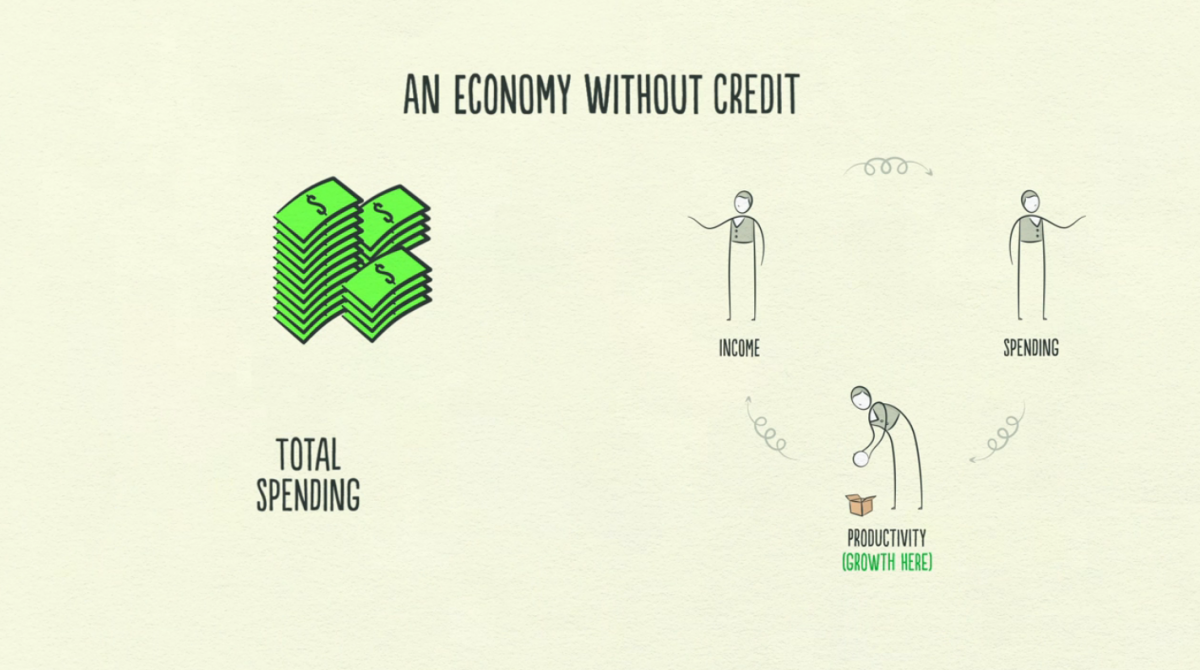

Nếu đó là một bức tranh u ám thì điều gì sẽ hiển thị trong một nền kinh tế mà không có tín dụng? Khi đó, con đường duy nhất để thúc đẩy chi tiêu (và tăng trưởng) sẽ là tăng năng suất.

If that's a grim picture, what would an economy without credit look like? Well, the only way to boost spending (and thus growth) would be to increase productivity

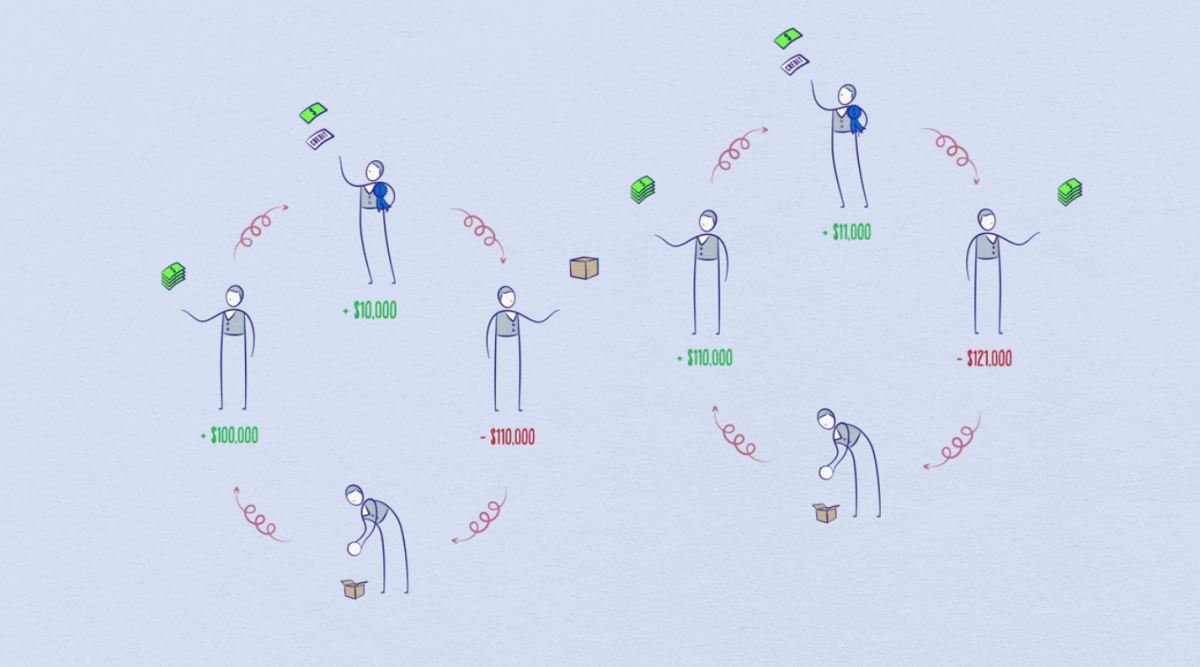

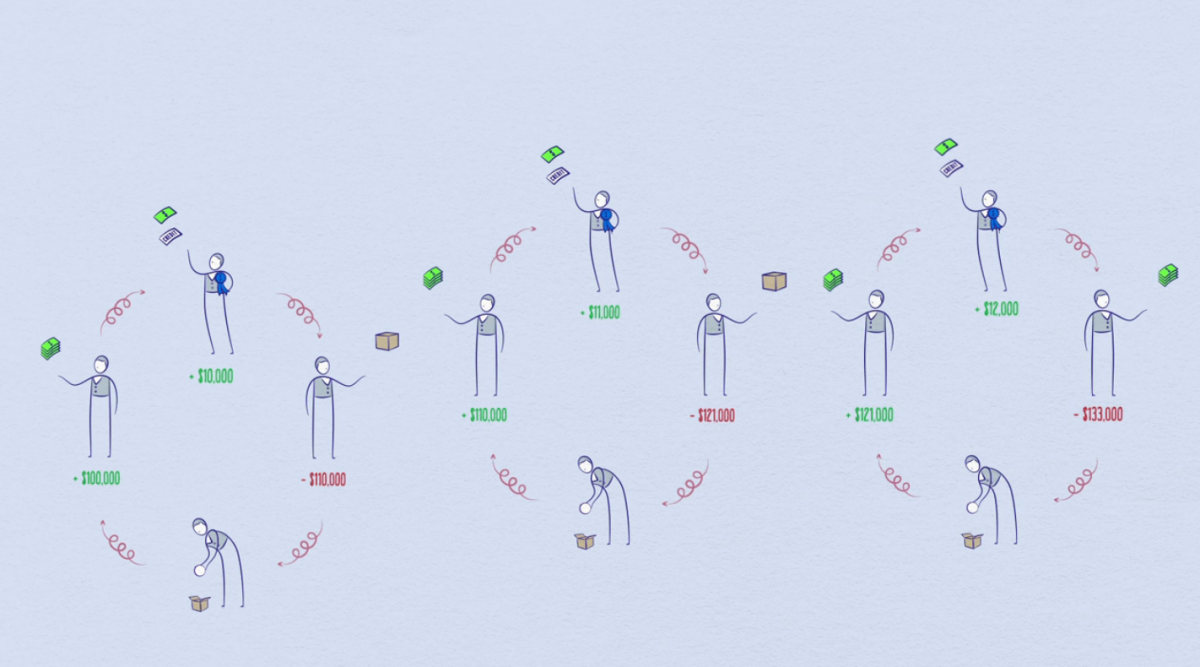

Nhưng chúng ta có một hệ thống tín dụng. Nếu tôi làm được 100,000 USD một năm, ngân hàng cho tôi mượn 10,000 USD tín dụng. Bây giờ tôi có 110,000 USD để chi tiêu. Và từ đó chi tiêu của tôi là thu nhập của bạn, bay giờ bạn đã kiếm được 110,000 USD và có thể mượn 11,000 USD từ ngân hàng.

But we have a credit system. If I make $100,000 a year, the bank gives me $10,000 in credit. Now I have $110,000 to spend. And since my spending is your income, now you have earned $110,000 and can get $11,000 from the bank

Và cứ thế. Chu kỳ tín dụng thúc đẩy tăng trưởng.

And so on. The credit cycle spurs growth

Nhưng ngân hàng trung ương không muốn mọi thứ ngoài tầm kiểm soát, và do vậy họ tăng và giảm lãi suất khi muốn khuyến khích hay hạn chế tổng tín dụng.

But the central bank doesn't want things to get out of hand, and so it raises and lowers interest rates to either promote or lessen the amount of borrowing

Bởi vì ngân hàng trung ương phải theo dõi gánh nặng nợ nần

Because a central bank has to keep an eye on the debt burden

Lưu ý cái cách của năm 2008, gánh nặng nợ nần đã vượt tầm kiểm soát. Những điều kiện cho vay đã quá dễ dãi và người ta đã mượn tiền quá mức. Chỉ còn một con đường duy nhất để đi kể từ đây.

Notice how in 2008, the debt burden was out of control. Lending conditions were too easy and people borrowed too much. There's only one way to go from here

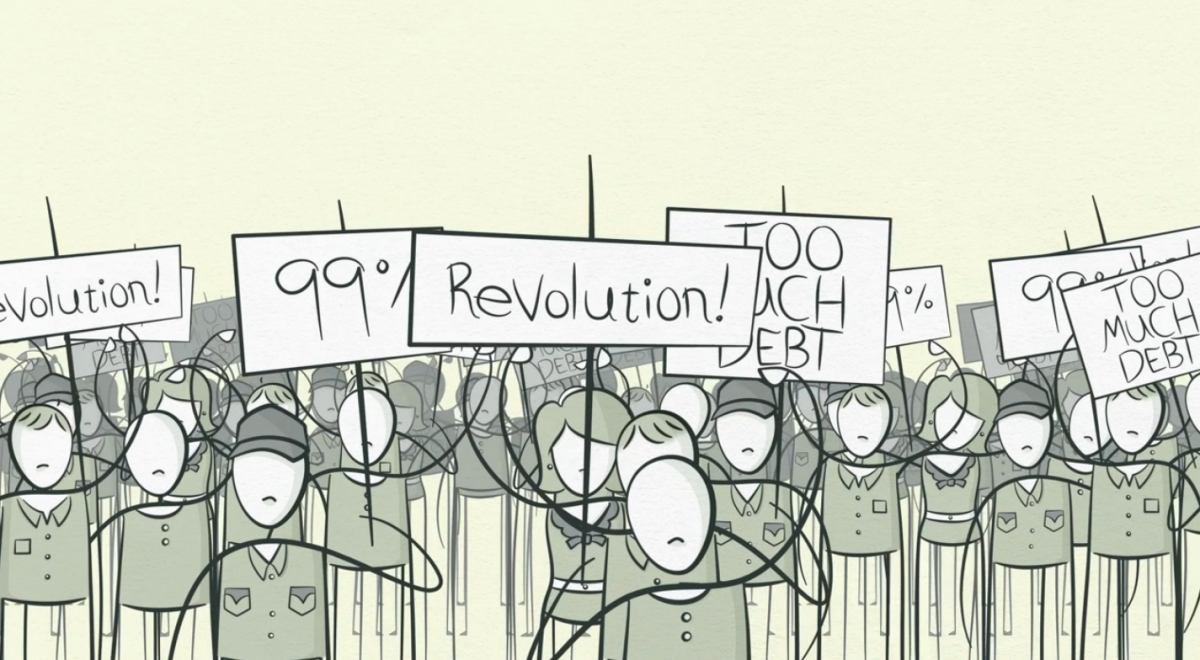

Khi mọi thứ bắt đầu quá đà, bạn có thể nhận lấy suy thoái và bất ổn xã hội.

When things start heading south, you can get a recession and social unrest

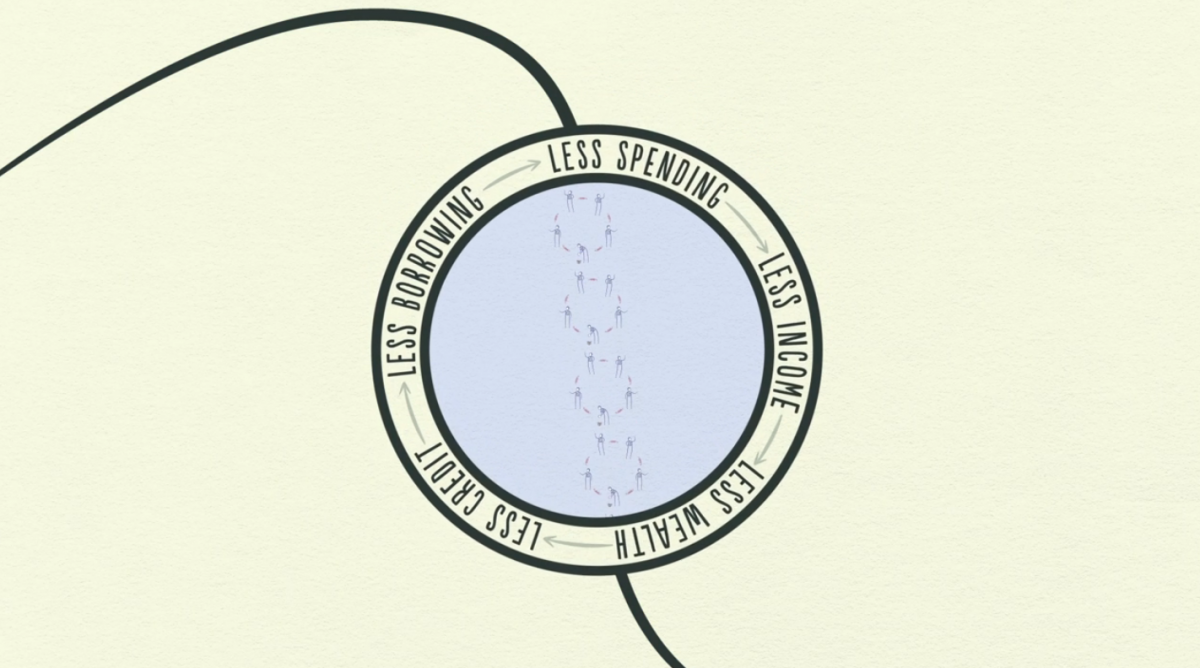

Hệ thống được kéo vào “thiết lập lại”. Điều đó được gọi là deleveraging, và đó cũng là những gì diễn ra sau khủng hoảng tài chính.

The system is forced to unwind. It's called deleveraging, and it's what happened after the financial crisis

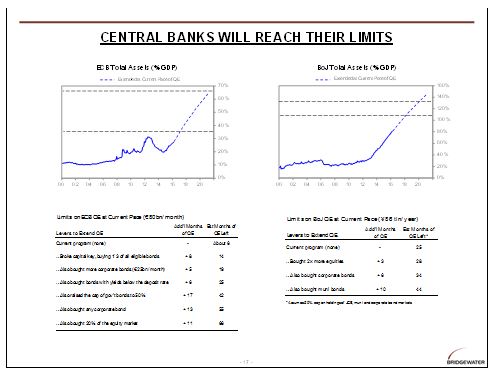

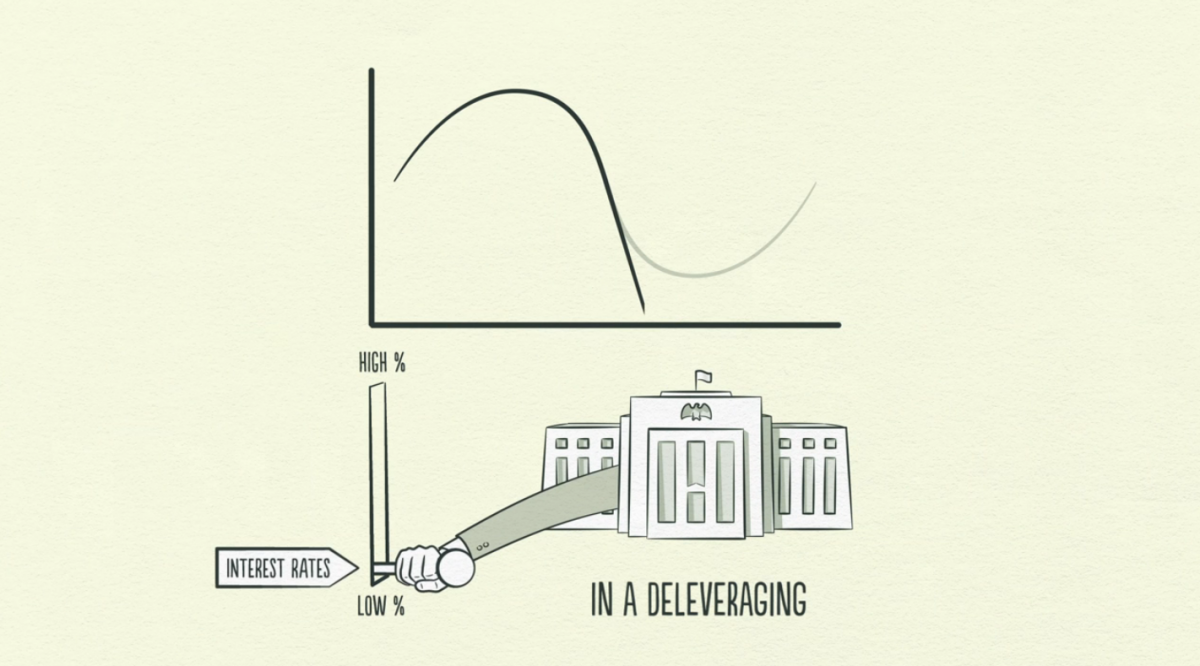

Bây giờ chúng ta muốn giảm tín dụng, nhưng vấn đề ngân hàng trung ương đã đẩy lãi suất về mức thấp.

Now we want to kick borrowing into gear, but the problem is that the central bank has pushed interest rates as low as they can go.

Những ngân hàng lo ngại nếu người đi vay có thật sự trả lại tiền.

Banks worry if they can actually get paid back. Borrowing suffers

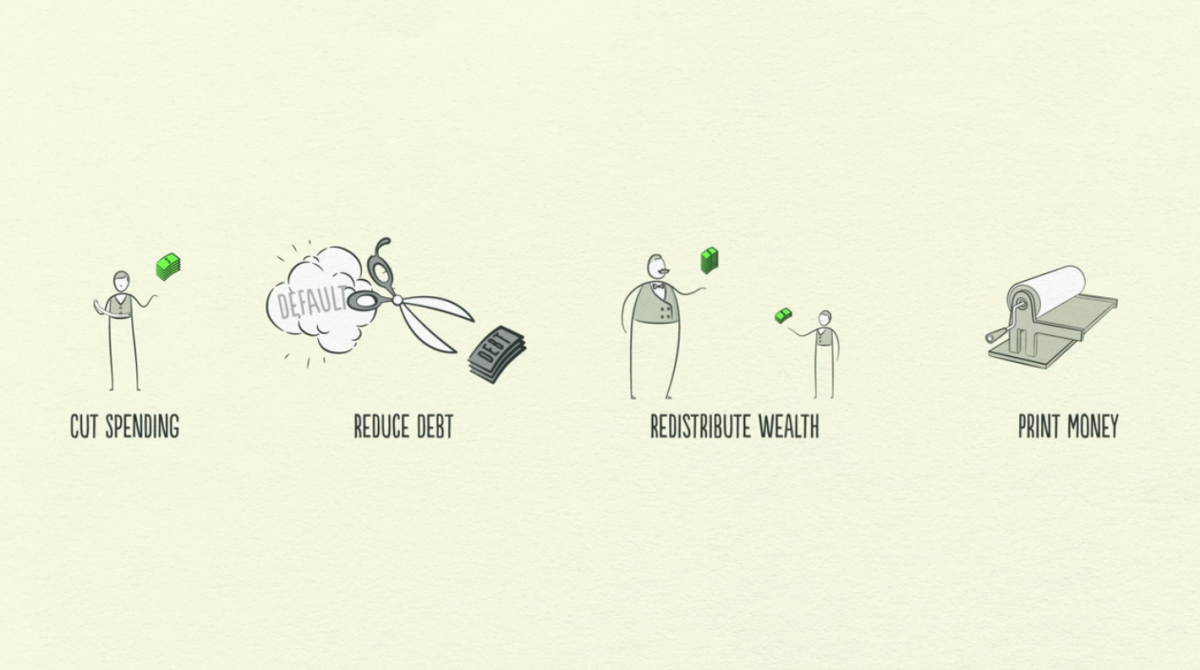

Có 4 cách để giảm nợ. Hầu hết mọi người có cảm giác thích thú với lựa chọn cuối (in tiền) bởi vì nó cảm giác tốt nhất trong ngắn hạn.

There are four ways to deleverage. Most people have an appetite for the last option (print money) because it feels the best in the short term

Một cách chúng ta giảm nợ nữa là thông qua tái cấu trúc nợ. Cơ bản, những ngân hàng thích có 1 chút gì đó hơn là không có gì.

One way we delever is through debt restructuring. Basically, banks would rather have some of something than all of nothing

Chính phủ và người dân có thể cắt chi tiêu. Chúng ta biết điều này như sự thắt lưng buộc bùng. Chính phủ cũng có thể phân phối lại tài sản cho dân Main Street, hi vọng rằng sẽ giúp tăng trưởng kinh tế khi người dân chi tiêu nhiều hơn.

The government and households can cut spending. We know this as austerity. The government can also redistribute wealth to Main Street, hoping that will help grow the economy as people spend more

Điều đó có nghĩa bạn phải rang thuế cho người giàu. Mọi người bắt đầu thù địch lẫn nhau.

That means you have to raise taxes on the wealthy. Everybody starts to resent each other

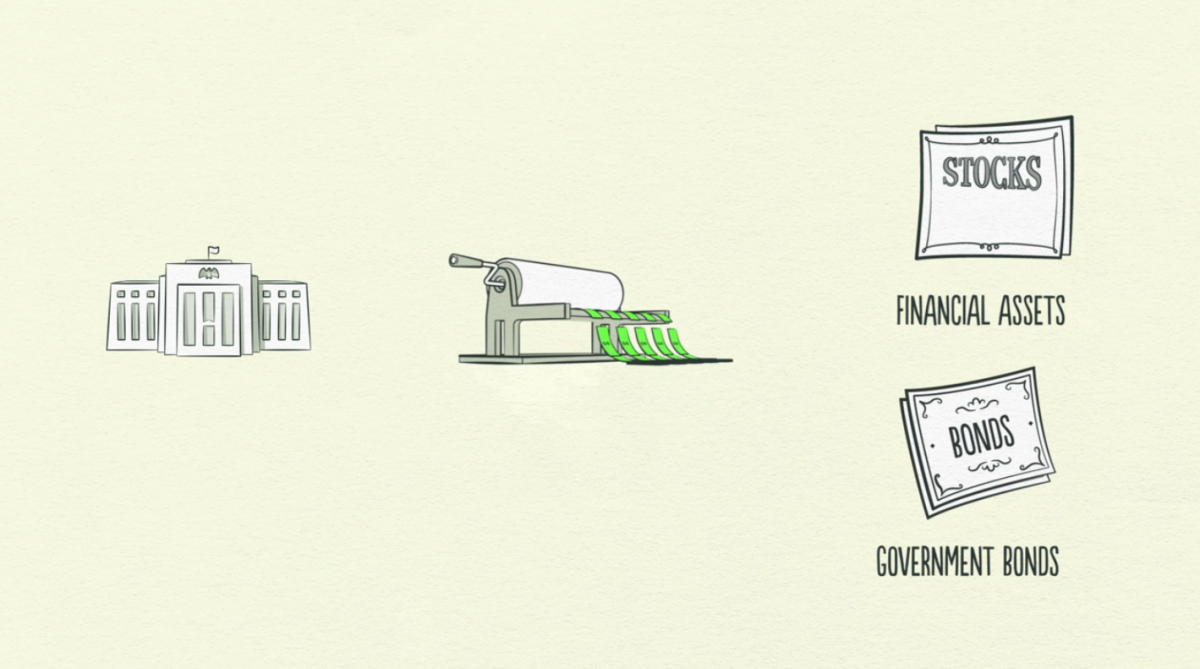

Ngân hàng trung ương cũng mua tài sản tài chính và trái phiếu chính phủ. Điều này giúp nới lỏng hệ thống tiền tệ.

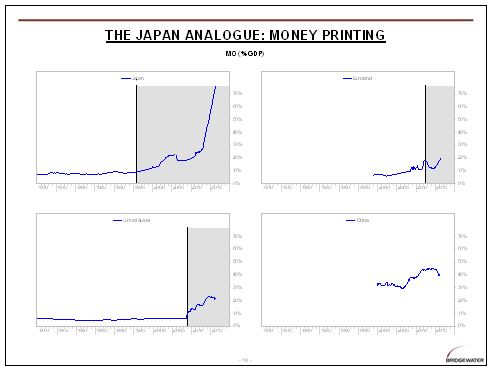

The central bank also buys up financial assets and government bonds. This helps ease the system

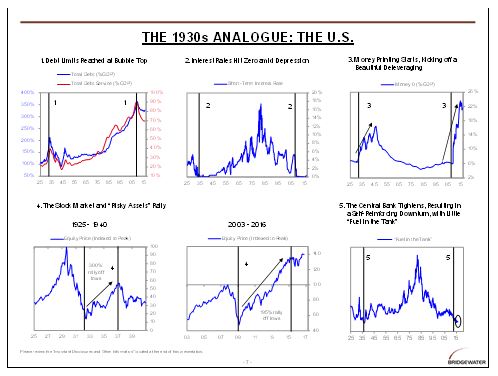

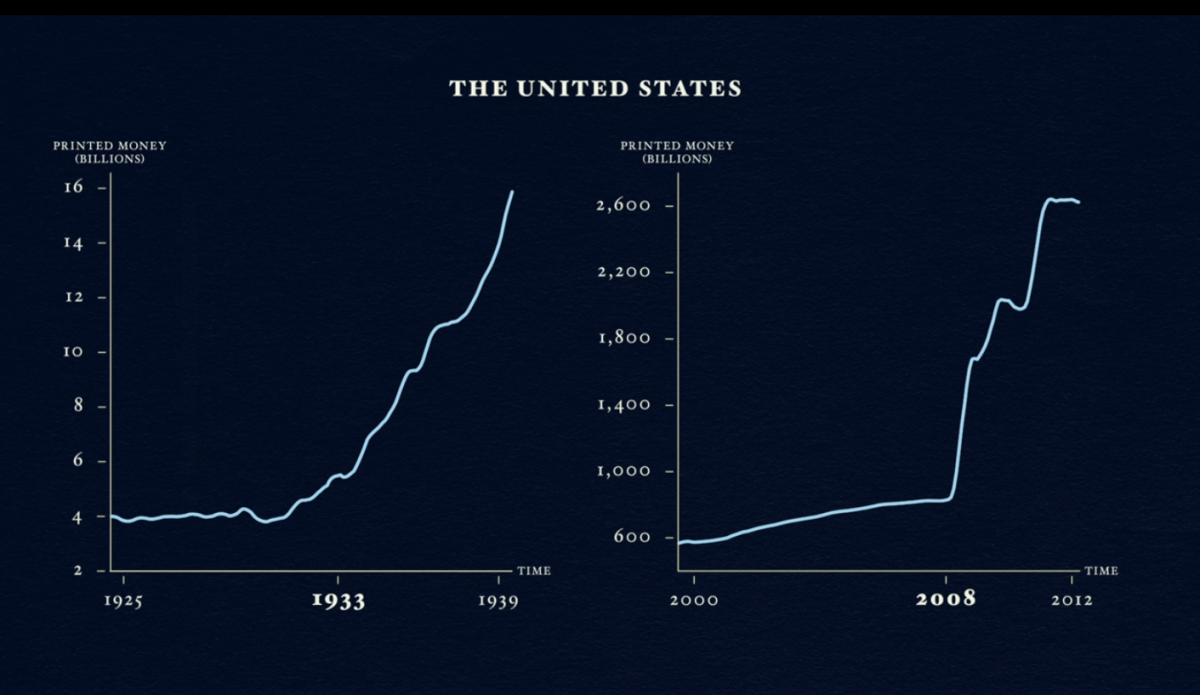

Nước Mỹ đang làm thế và tiến trình đó được biết đến với tên “nới lỏng định lượng”. Như bạn thấy, phản ứng với khủng hoảng tài chính này tương tự như những năm 1930s.

The U.S. is doing it now in a process known as quantitative easing. As you can see, the reaction to this financial crisis resembles the 1930s

Vì vậy, những gì tạo một chu kỳ được gọi “beautiful” deleveraging?

So what makes a cycle a so-called "beautiful" deleveraging?

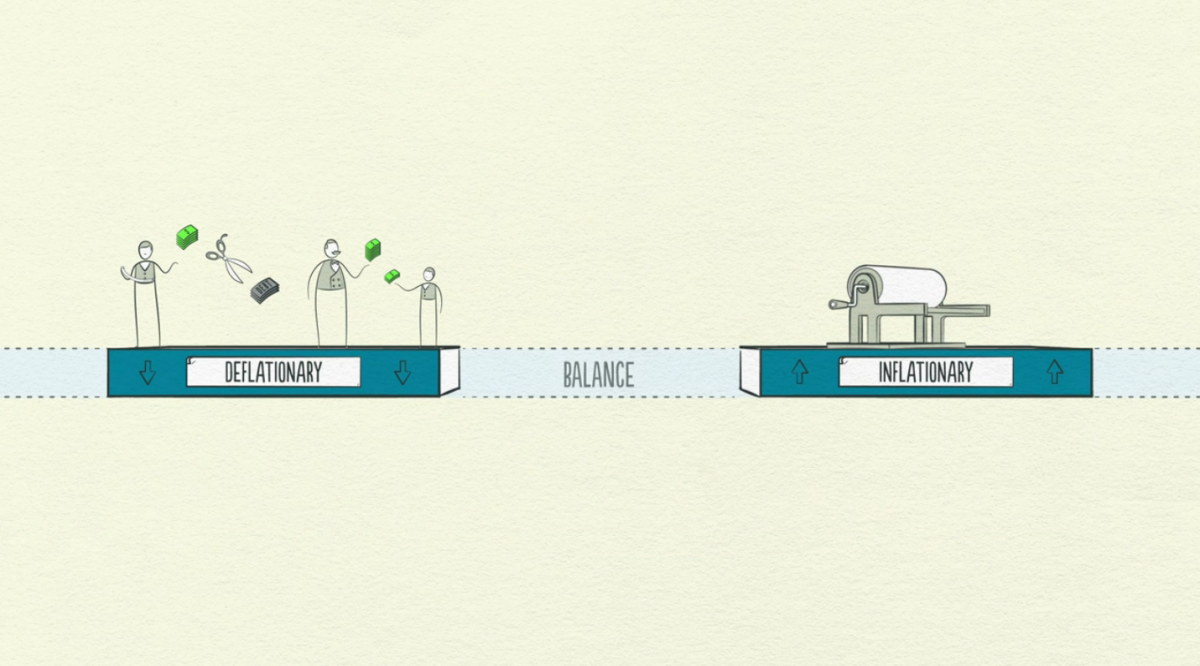

Có sự cân bằng đúng đắn giữa những thước đo giảm phát (thắt lưng buộc bụng, tái cơ cấu nợ, phân phối lại thu nhập) và thước đo lạm phát (in tiền, chính sách mua trái phiếu của ngân hàng trung ương).

It's the right balance between deflationary measures (austerity, debt restructuring, income redistribution) and inflationary measures (printing money, central bank bond-buying).

Các bạn muốn thu nhập tăng nhanh hơn hợ, vì vậy quốc gia sẽ lại trở về trạng thái đáng tin cậy để cho vay. Những ngân hàng sẽ cho vay và người ta có thể vay mượn.

You want income to increase at a higher rate than debt, so that the country is "creditworthy" again. Banks will lend and people can borrow

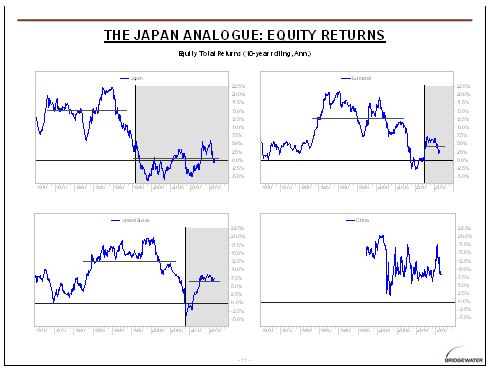

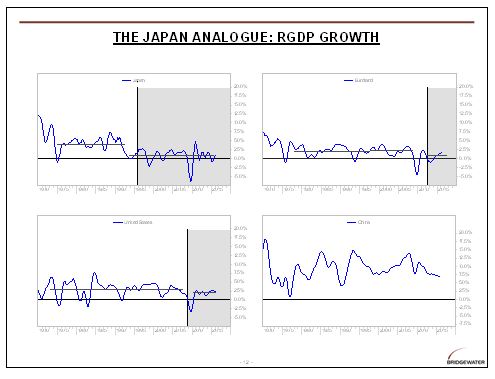

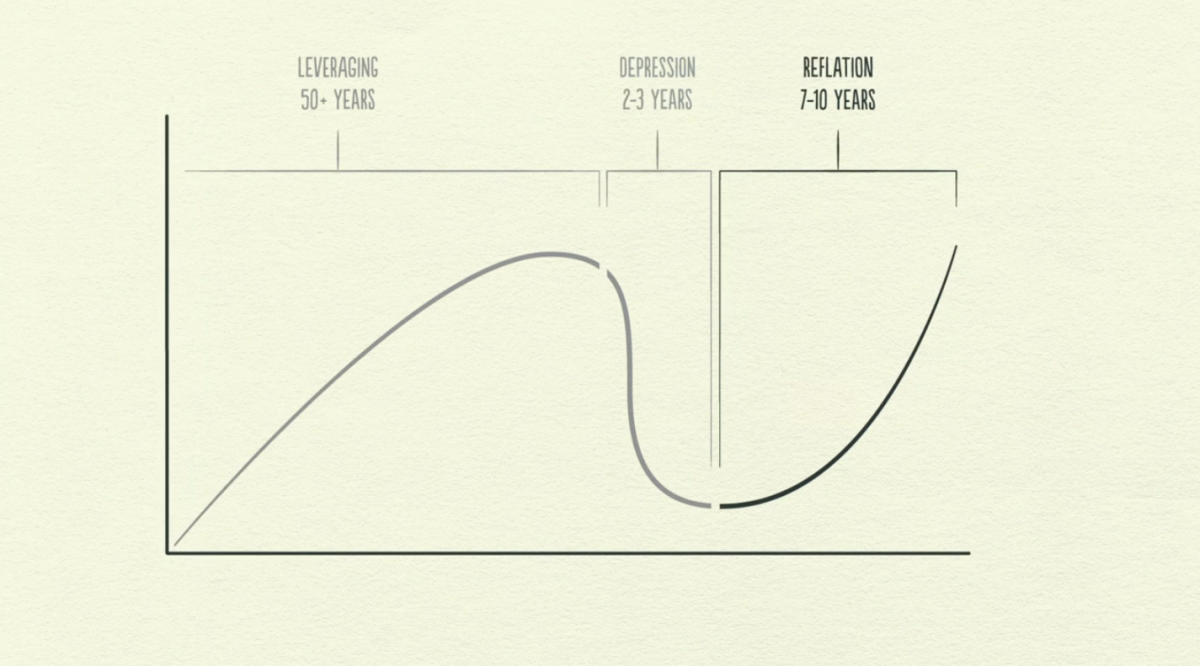

Kiểm tra suy nghĩ về thời điểm. Quá trình giảm nợ sẽ lâu dài, đôi khi được biết đến như “thập kỷ mất mát”

Check out the timing though. Deleveraging takes a long period of time sometimes known as a "lost decade."

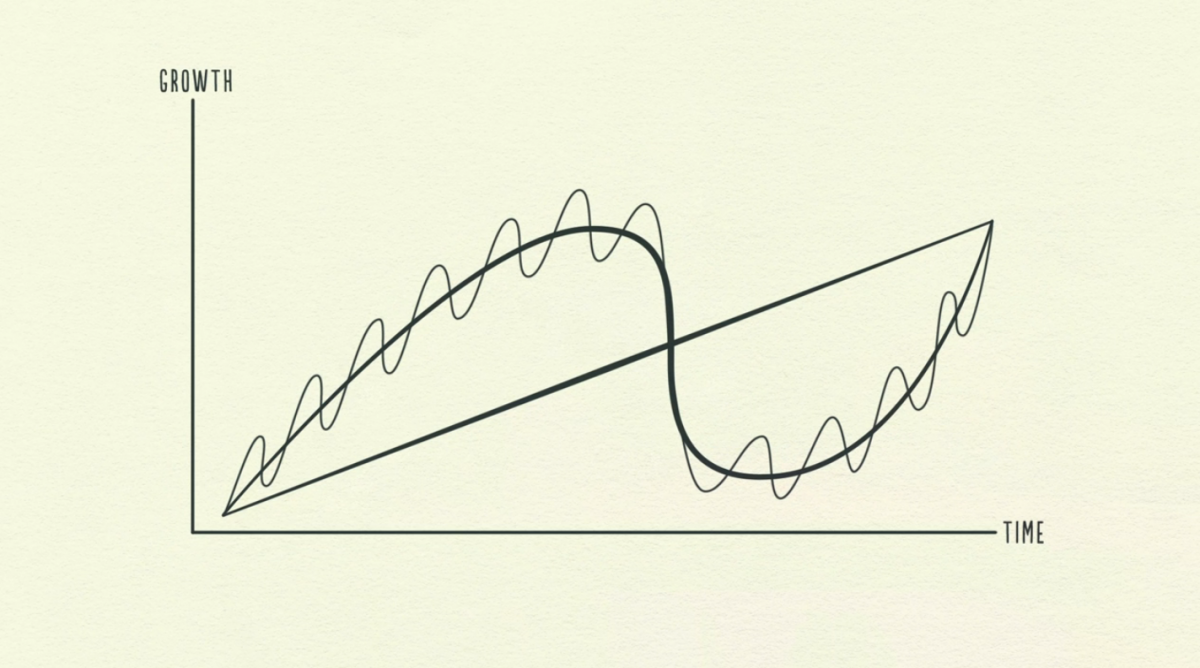

Với Dalio, đây là một template quan trọng. nợ ngắn hạn, nợ dài hạn và tăng trưởng năng lực sản xuất. Kết hợp 3 đường này lại bạn có thể biết chúng ta đã ở đâu, đang ở đâu và sẽ đi về đâu.

For Dalio, this is the key template. Short-term debt, long-term debt, and the productivity growth line. Looking at these three lines in conjunction can show you where we've been, where we are now, and where we're headed.

Nếu nợ tăng nhanh hơn thu nhập, gánh nặng nợ nần sẽ đè nặng bạn

If debts rise faster than income, debt burdens will crush you.

Nếu thu nhập tăng nhanh hơn năng lực sản xuất, cuối cùng rồi bạn sẽ trở nên kém cạnh tranh

If income rises faster than productivity, you'll eventually become uncompetitive

Trong dài hạn, nhân tố năng suất là quan trọng nhất. Tín dụng sẽ đến và đi nhưng năng suất vẫn leo lên ổn định. Điều đó đến cho cả những chính phủ và cho cả các cá nhân.

In the long run, productivity matters most. Credit will come and go, but notice how productivity stays on a steady climb. That goes for governments and it goes for individuals

Hiểu kỹ bằng video sau:

Nguồn: finandlife|Business Insider

=============

is nothing more than: không gì hơn

Với tôi nền kinh tế không gì hơn là tổng hòa các quyết định mua bán, muốn hiểu nền kinh tế hiện tại như thế nào ta phải hiểu hết tất cả giao dịch, tại sao người mua lại mua, tại sao người bán lại bán.

to put ourselves in the shoes of: đặt vị trí của mình vào…

Nhìn vào người mua để hình dung bao nhiêu tiền (gồm tiền của họ và tín dụng) phải bỏ ra, nhìn vào người mua để hình dung bao nhiêu sản lượng họ phải bán. Giá chính là lấy tổng tiền chi tiêu chia cho tổng hàng hóa bán.

1. Tăng trưởng của năng suất

2. Chu kỳ nợ ngắn hạn: cũng được biết như chu kỳ kinh doanh, thường kéo dài 5-10 năm

3. Chu kỳ nợ dài hạn, thường kéo dài 50-75 năm. Cài này có liên quan nhiều hơn đến chu kỳ dân số học. Khi nền kinh tế ở tình trạng sinh đẻ cao, đến dân số trẻ, đến dân số vàng, đến dân số già. Thì đi kèm với đó, là trạng thái kinh tế khó khăn vì phải chăm lo quá nhiều con nít, đến càng khó khăn hơn vì con nít đó và tuổi ăn tuổi học, sau đó, thì khỏe, vì con nít đó vào tuổi đi làm và bắt đầu chi tiêu mạnh giúp nền kinh tế khỏe mạnh. Khi đạt độ dân số vàng, mức độ chi tiêu và lao động của tầng lớp trẻ này rất khủng khiếp sẽ giúp nền kinh tế cảm giác giàu có kinh khủng. Khi lớp trẻ già đi, nhịp tiêu dùng giảm, bắt đầu những khoản chi phí liên quan đến y tế ngày càng nhiều, kinh tế suy yếu lần.

Trong 3 cái này, chu kỳ nợ dài hạn là ít người hiểu nhất, vì nó diễn ra quá dài, cả đời người.

Ba cân bằng quan trọng mà nền kinh tế và thị trường phải xoay quanh:

1. Tăng trưởng của nợ phải phù hợp với tăng trưởng thu nhập

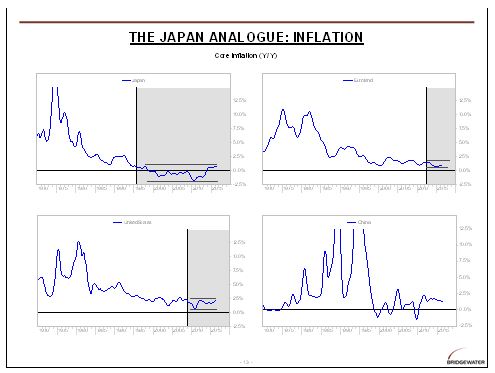

2. Lãi suất điều hành kinh tế và lạm phát không thể quá cao hoặc quá thấp trong thời gian dài, bởi vì nếu một nền kinh tế khủng hoảng hoặc tăng trưởng nóng trong thời gian dài, nó sẽ dẫn đến điểm đảo chiều.

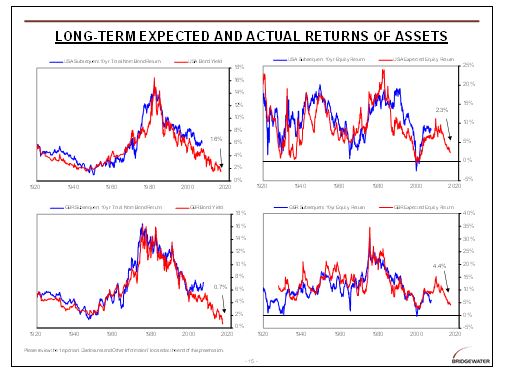

3. Tỷ suất sinh lợi kỳ vọng của chứng khoán phải lớn hơn trái phiếu và trái phiếu phải lớn hơn tiền mặt.

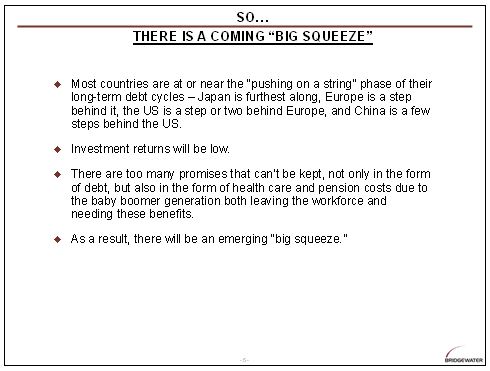

Thực trạng hiện tại thế nào:

1. Tăng trưởng năng suất thấp,

2. Chu kỳ nợ ngắn hạn/chu kỳ kinh doanh được đo bằng GDP gaps gần với điểm giữ hơn điểm thái quá/cực đoan.

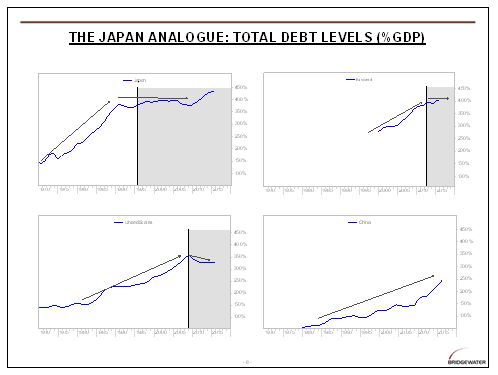

3. Chu kỳ nợ dài hạn đang tiếp cận vùng cảnh sau khi nợ không thể được tăng thêm và ngân hàng trung ương đang tiếp cận bằng cánh đẩy đến giới hạn.

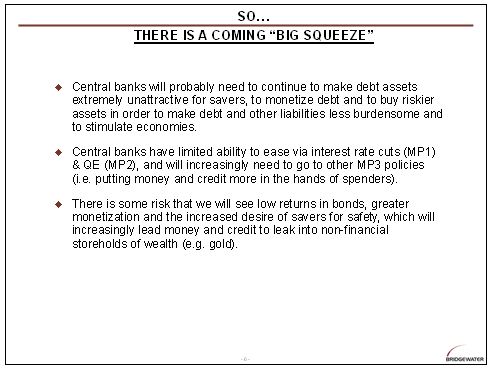

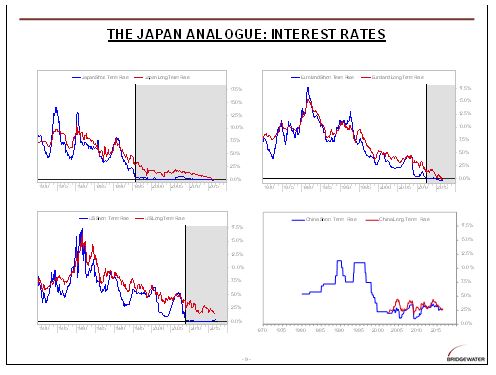

Các ngân hàng trung ương đang đẩy tới giới hạn bởi vì lãi suất về vùng thấp nhất và hiệu quả của các QEs đang đẩy tới hạn khi phần bù rủi ro và spreads đang nén chặt. Việc đẩy tiến cho vay đến người tiêu dùng gặp nhiều thách thức, đây là vấn nạn toàn cầu hiện nay. Nhật Bản đang gần nhất đến giới hạn, sau đó là Châu Âu, sau đó là Mỹ, cuối cùng là Trung Quốc.

Chỉ cần một sự tăng nhẹ của lãi suất trái phiếu chính phủ sẽ làm giá trái phiếu và các tài sản khác giảm rất nhanh. Bởi vì, giá các tài sản này giờ đây cực kỳ nhạy cảm với lợi suất. Khi lợi suất tăng lên sẽ làm thay đổi suất chiết khấu trong mô hình định giá, và suất chiết khấu ảnh hưởng lên tất cả kỳ hạn và trong thời gian vô số dài sau đó, làm giá hiện tại rớt ngay lập tức.

Tại lúc này, trái phiếu trở thành thương vụ tệ và ngân hàng trung ương cố đẩy tiền vào thị trường, yield giảm thấp hơn và rủi ro giá cả tăng cao trong tương lai, người tiết kiệm có thể quyết định bỏ đi. Tại lãi suất hiện thời, ngân hàng trung ương sẽ sớm tới giới hạn. Hiện tại, những tài sản rủi ro hơn nhìn hấp dẫn trong mối tương quan với trái phiếu và tiền mặt, nhưng không rẻ trong tương quan với rủi ro.